I know a lot of smart people.

I also know a lot of people that think they're smarter than they are (even the smart ones ... or, perhaps, especially the smart ones).

It's common. So common, in fact, that there's a name for it. The Dunning-Kruger Effect.

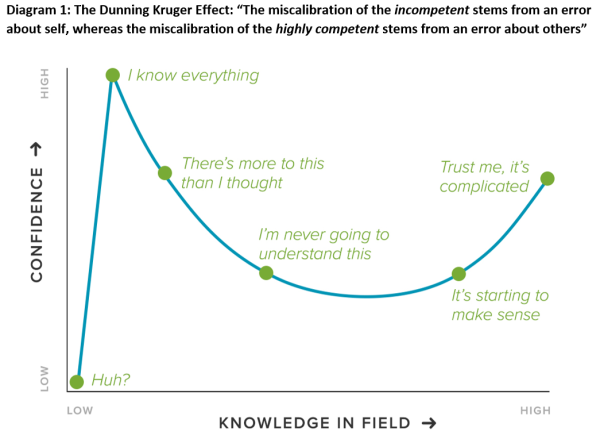

Have you ever met someone who's so confident about what they think that they believe they know more than an expert in a field? That's the Dunning-Kruger effect. It's defined as a cognitive bias where a lack of self-awareness prevents someone from accurately assessing their own skills.

Here's a graph that shows the general path a person takes on their journey towards mastery of a subject.

via NC Soy

via NC Soy

The funny thing about the above image... it's actually not a literal part of the paper on the Dunning-Kruger Effect. But it's now so commonplace that people report that chart as fact. A fitting example of the effect.

David Fitzsimmons via Cagle Cartoons

David Fitzsimmons via Cagle Cartoons

In our daily lives, it can often be funny or frustrating to see the "victims" of this effect, but I'd warn you that we all have times where we're prone to this; and it's a sign of ignorance, not stupidity.

This is a problem with all groups and all people. Even if you already know about the cognitive bias resulting from the Dunning-Kruger Effect, you're not immune.

It should be a reminder to reflect inward - not cast aspersions outward.

Two different ways that people get it wrong, first is to think about other people and it’s not about me. The second is thinking that incompetent people are the most confident people in the room, that’s not necessarily true.

Usually, that shows up in our data, but they are usually less confident than the really competent people but not that much... - David Dunning

To close out, even this article on the Dunning-Kruger presents a simplification of its findings. The U-shape in the graph isn't seen in the paper, the connection that lack of ability precludes meta-cognitive ability on a task is intuitive, but not the only potential takeaway from the paper.

Regardless, I think it's clear we are all victims of an amalgam of different cognitive biases.

We judge ourselves situationally, and assume "the best". Meanwhile, we often assume "the worst" of others.

We can do better ... it starts with awareness.

Progress starts by telling the truth.

The Art and Science of Economics

Today, I want to focus on one issue that's a commonality in trading and economics.

It's the tendency for us, as humans to create stories about why things happen ... even in the absence of enough data to .

The Federal Reserve Chairman, Jerome Powell, gave a speech in October with a dizzying amount of statistics. His portion starts around the 9:30 mark.

via Yahoo Finance

In this talk, he mentions a lot of interesting stats, but notice how many are focused on the change (or rate of change) within a relatively small window of the available data.

Also, notice how he crafts a story around the direction of the numbers rather than acknowledging or contextualizing the numbers themselves. This isn't inherently bad – but it's something to be aware of when interpreting what it means to you.

When making decisions, the direction and intensity of movement are important, but so are more objective measures.

Stories can help make us comfortable with a temporarily bad situation, but if you get lost in the story and aren't cognizant of the bad situation, it can be harder to correct.

In trading, traders often tell themselves stories about why a movement happened, but markets and economies are more complicated than any heuristic. Those stories can be helpful retroactively - but they're rarely a powerful predictor.

Economics and trading both have hard sciences behind them. You can look at technical indicators, you can look at historical events, and you can build algorithms with advanced technology that look for the patterns you miss. But it's what you do with those inputs that matters.

Mark Perry wrote an article about why "it’s really hard to ‘beat the market’ over time." In it, he states that over the 15-year investment horizon, 92.43% of large-cap managers, 95.13% of mid-cap managers, and 97.70% of small-cap managers failed to outperform on a relative basis. Stated differently, over those 15 years (from June 30, 2003 to June 30, 2018), only one in 13 large-cap managers, only one in 21 mid-cap managers, and one in 43 small-cap managers were able to outperform their benchmark index.

It’s hard to admit to yourself that you aren't better than average. Nonetheless, over any period of time, this is true for half of us. This "truth" is especially hard to accept for people who have achieved a lot in their lives and have the money to invest.

The trick is to find a way to separate "luck" from "skill" ... or to avoid being fooled by randomness.

We live in interesting times! The signal-to-noise ratio is already tough to deal with ... and I suspect that we are in a period where we have to expect even more noise.

I've written a couple of posts on Economics that might help. Here are a few of the more popular ones, if you are interested.

What stories are you telling yourself about the economy? About the markets? About the election?

There's a difference between guessing and knowing, and knowing is more profitable!

Be careful!

Posted at 05:17 PM in Business, Current Affairs, Ideas, Market Commentary, Science, Trading, Trading Tools | Permalink | Comments (0)

Reblog (0)