Here are some of the posts that caught my eye recently. Hope you find something interesting.

Lighter Links:

Trading Links:

Here are some of the posts that caught my eye recently. Hope you find something interesting.

Lighter Links:

Trading Links:

Posted at 10:56 PM | Permalink | Comments (0)

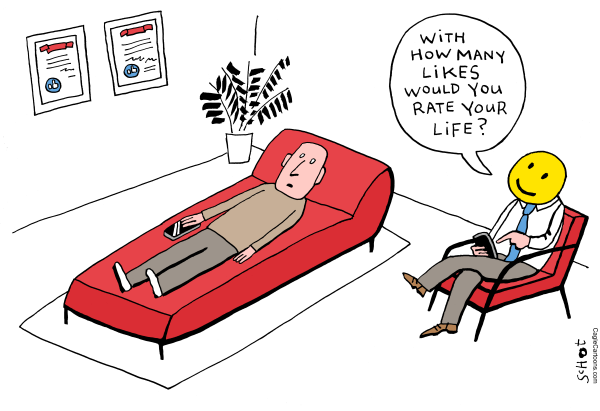

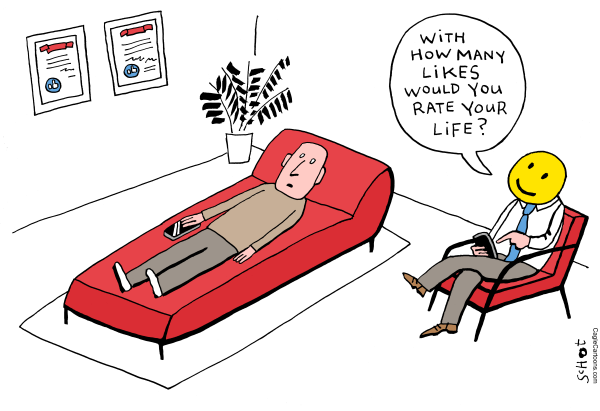

I am often amazed at how little human nature has changed throughout recorded history.

Despite the exponential progress we’ve made in health, wealth, society, tools, and understanding ... we still struggle to find meaning, purpose, and happiness in our lives and our existence.

Last month, I shared an article on Global Happiness Levels in 2025. Here are a few bullets that summarize the findings:

Upon reflection, that post didn’t attempt to define happiness. This post will focus on how to do that.

While it seems like a simple concept, happiness is complex. We know many things that contribute to and detract from it; we know humans strive for it, but it is still surprisingly challenging to put a uniform definition on it.

A few years ago, a hobbyist philosopher analyzed 93 philosophy books, spanning from 570 BC to 1588, in an attempt to find a universal definition of Happiness. Here are those findings.

via Reddit.

It starts with a simple list of definitions from various philosophers. It does a meta-analysis to create some meaningful categories of definition. Then it presents the admittingly subjective conclusion that:

Happiness is to accept and find harmony with reason.

My son, Zach, pointed out that while “happiness” is a conscious choice, paradoxically, the “pursuit of happiness” often results in unhappiness. Why? Because happiness is a result of acceptance. However, when happiness is the goal, you often focus on what you’re lacking instead of what you already have. You start to live in the ‘Gap’ instead of the ‘Gain’.

So, it got me thinking – and that got me to play around with search and AI, a little, to broaden my data sources and perspectives. If you would like to view the raw data, here are the notes I compiled (along with the AI-generated version of what this article could have been, had it been left to AI, rather than me and Zach).

Reach out – I’m curious to hear what you think!

Posted at 08:01 PM in Books, Business, Current Affairs, Healthy Lifestyle, Ideas, Just for Fun, Personal Development, Religion, Science, Writing | Permalink | Comments (0)

Here are some of the posts that caught my eye recently. Hope you find something interesting.

Lighter Links:

Trading Links:

Posted at 10:59 PM | Permalink | Comments (0)

The U.S. Treasury is ceasing production of pennies - as they cost more to make than they’re worth.

According to a 2024 report from the U.S. Mint, we lose $85M a year minting pennies, as they cost 3.69 cents to make.

That makes the phrase “penny wise and pound foolish” officially passé - at least in America.

Many phrases like this still exist. It’s an interesting example of the power of language. Words take on meaning beyond their original usage ... and often remain relevant long after their origin has become irrelevant.

For example:

Until recently, technologies (and the phrases they spawned) lasted for decades, if not longer. As technology evolves at an ever-accelerating pace, new tools, platforms, and ways of communicating emerge almost daily. With these innovations come fresh slang, buzzwords, and cultural references that often catch on quickly—think “DM me,” “ghosting,” or “cloud computing.” Yet just as rapidly as they rise, many of these terms fade into obscurity, replaced by the next wave of trends. What was once cutting-edge can become outdated in a matter of years, if not months. This cycle of innovation and obsolescence is a hallmark of the modern digital era.

However, much like these old idioms, the fleeting nature of these technologies and jobs doesn’t mean they lack value or impact. Some expressions endure because they capture something universally human—emotion, conflict, humor—even if the context changes. Similarly, technologies may evolve, but their core functions or purposes often remain. The fax machine gives way to email, and email to instant messaging—but the need for communication is constant.

This principle also applies to work and tools. While job titles and methods may change, the underlying skills — such as critical thinking, collaboration, and creativity — remain timeless. A carpenter today might use laser-guided saws instead of hand tools, just as a marketer might use data analytics instead of intuition alone, but the essence of their work persists. Innovation reshapes how we do things, not always what we do.

Just as enduring phrases carry forward old meanings in new settings, so too will jobs, tools, and skills adapt and survive.

Onwards!

Posted at 04:10 PM in Books, Current Affairs, Film, Gadgets, Ideas, Just for Fun, Personal Development, Science, Web/Tech, Writing | Permalink | Comments (0)

The last time I talked about AI Art specifically was in 2022 when Dall-E was just gaining steam. Before that, it was 2019, when AI self-portraits were going viral.

On both occasions, it still felt like the relative infancy of the technology. I compared it to VR getting another 15 minutes of fame.

The images at the time weren’t fantastic, but it was a massive step in AI’s ability to understand and translate text into a coherent graphic response. The algorithms still didn’t really “understand” the meaning of images the way we do, and they were guessing based on what they had seen before - which was much less than today’s algorithms have seen. They were also much worse at interpreting images. As such, when you tried to use AI to recreate an image, there were a lot of hallucinations. The algorithms were essentially a brute-force application of math masquerading as intelligence.

Fortunately, AI imagery has come a long way since then. However, with that improvement comes more ethical concerns.

The rise of AI-generated art has sparked a complex and ongoing ethical debate, with compelling arguments on both sides. At the heart of the discussion lies the question of authorship, originality, and the impact of automation on human creativity and labor.

Proponents of AI art argue that it represents a powerful extension of human imagination. Just as past innovations—such as photography, digital editing, or sampling in music—were initially met with skepticism, Advocates argue AI-generated art is simply the next evolution in the artistic toolkit, and it democratizes access to artmaking. As a result, those with less skill - or time - can explore new styles, generate concepts, and be creative in a new form. To this end, they see AI not as a threat but as a collaborator—another brush or chisel in an artist’s hand.

However, critics raise concerns about the ethical implications of AI art, particularly in how these models are trained. Many AI systems are built on vast datasets scraped from the internet, including artwork by human creators who were neither consulted nor compensated, leading to accusations of IP theft. Moreover, they argue it sets a dangerous precedent where creative works can be replicated and commodified without consent or attribution. Lastly, on the idea of democratization, they would argue that art is already accessible to all and that people should be willing to explore skills not only to be good at them but to enjoy them.

The most recent trend has been a great example of this argument. The launch of OpenAI’s new image generator, powered by GPT-4, has empowered users to transform their photos into various famous media themes - like Renaissance paintings or Studio Ghibli anime images - which ironically goes against the ethos of Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki. The studio is known for its commitment to the craft, with carefully animated and hand-drawn scenes. Their films are known for glorifying nature and living in harmony with it. Miyazaki also believes that AI art is disrespectful to the “life” found in human-created art.

“I feel like we are nearing the end times. We humans are losing faith in ourselves.” - Hayao Miyazaki

I’m a massive fan of AI - and even AI art ... but as the technology continues to evolve, society must grapple with how to integrate these tools in ways that honor both progress and the rights of the artists (and people) whose work—and livelihoods—may be at stake.

What do you think?

Posted at 01:07 AM in Art, Business, Current Affairs, Film, Gadgets, Games, Ideas, Just for Fun, Market Commentary, Movies, Music, Pictures, Science, Web/Tech | Permalink | Comments (0)

Here are some of the posts that caught my eye recently. Hope you find something interesting.

Lighter Links:

Trading Links:

Posted at 01:04 AM | Permalink | Comments (0)

It only takes a quick look at Veo 3 to realize it represents a significant breakthrough in delivering astonishingly realistic videos.

I’m only including two examples here ... but I went down the rabbit hole and came away very impressed.

via Jerrod Lew

It is becoming easier for almost anyone to create the type of content that only a specialist could produce before. The tool makes it easy in these three ways.

If you want to play with it, it’s available to Google Ultra subscribers through the Gemini app and Google Labs.

Ok, but what can it do?

Hashem Al-Ghaili via X

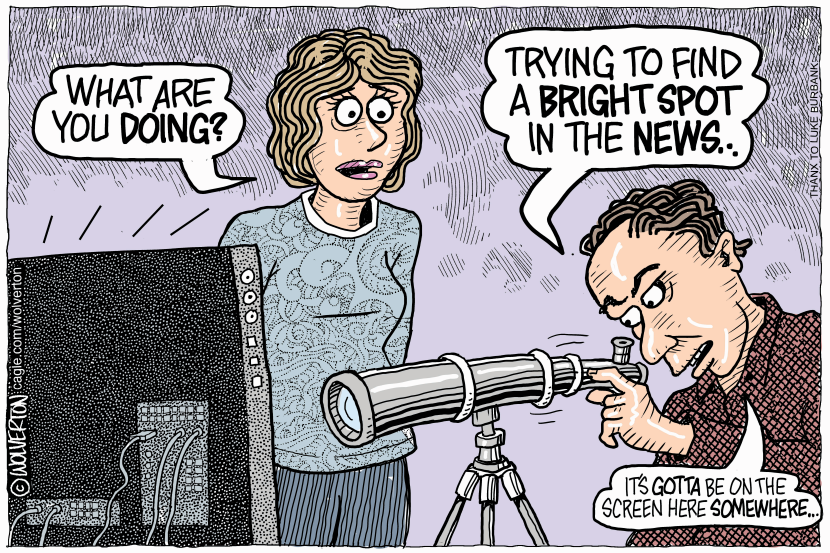

I predict you will see a massive influx of AI-generated content flooding social media using tools like this.

Posted at 04:13 PM in Art, Business, Current Affairs, Film, Gadgets, Games, Healthy Lifestyle, Ideas, Just for Fun, Market Commentary, Movies, Music, Pictures, Religion, Science, Television, Trading, Web/Tech | Permalink | Comments (0)

Here are some of the posts that caught my eye recently. Hope you find something interesting.

Lighter Links:

Trading Links:

Posted at 08:57 PM | Permalink | Comments (0)

At the core of Capitalogix’s existence is a commitment to systemization and automation.

At first, the goal was to eliminate fear, greed, and discretionary mistakes from trading.

Over time, we’ve worked hard at making countless things easier. Much like math, we found that the best practice is to simplify complex processes before trying to automate them.

I’m surprised by how many times I have had the same realization ... Less is more.

Likewise, I’ve learned the hard way that a great strategy is useless if people don’t get it. That is part of the reason that frameworks are so important.

Ultimately, the process, the system, and the automation should follow this basic recipe if you want it to succeed: Simple, Repeatable, Consistent, and Scalable.

Finding ways to automate sounds great. Increasing efficiency, effectiveness, and certainty sounds great, too ... but, routines and habits become ruts and limits when they become un-measured, un-managed, or forgotten.

A practical reality of increasing automation and constant progress is that it becomes increasingly important to have expiration dates on decisions, systems, components, and automations. We need to shine a light on things to make sure they still make sense or to determine whether we have a better option.

Freeing humans to create the most value sounds great, too ... but, as the pace of technological progress increases, the importance of freeing people to do more diminishes if they don’t actively rise to the occasion.

My Use of Technology

I got my first computer in 1984. It was the original Macintosh. That means I’ve been searching for and collecting technology tools to make business and life easier and better since the mid-80s.

It has been a long and winding road. These days, it seems like I’m constantly looking for new ways to use AI in my life.

As you might guess, I “play” with a lot of tools. Of course, I think of it as research, discovery, and skill-building ... rather than playing. Why? Because it is something I’m good at, it produces value – and it gives me energy ... so, I make sure to reserve a place for it in my routine.

While most of what I explore doesn’t make it into my “real work” routine, I now have a toolbox of dozens of tools that I use for everything from research, notetaking, brainstorming, writing, and even relaxing.

It’s a little embarrassing, but my most popular YouTube video is an explainer video on Dragon NaturallySpeaking from 13 years ago. It was (and still is) dictation software, but from a time before your phone gave you that capability.

As I focus on systemization, I also have to focus on optimization.

Using generative AI tools for daily research has fundamentally changed how I approach information gathering. What began as a meditative practice—slowly reading, digesting, and reflecting on material—has evolved into a faster, more expansive process. With AI, I can now scan and synthesize a much broader set of sources in far less time. The quality of the summaries and takeaways is high, enabling me to deliver more value to others. I can write better articles, share timely insights with fellow business owners, and keep my team well-informed. The impact on others has grown — but something subtle has shifted in my own learning.

The tradeoff is that if I’m not as careful as I used to be while doing the research, and I don’t engage with the material in the same way I did before. When I did the research manually, I was “chewing and swallowing” each idea, pausing to make connections, reflecting on implications, and wrestling with the nuance. That process was slower, but it etched ideas more deeply into memory.

As a result, my favorite articles of the week or month would show up in how I spoke on stage, what I wrote about, and how I worked through roadblocks with employees. Now, I notice that although I’m exposed to more information, it doesn’t have the same weight or impact. I’m consuming more at scale ... but retaining less, or perhaps less deeply (at least in my head). In contrast, I store much more, both in terms of quantity and depth, in my second brain (meaning, the digital repositories available for search when needed).

This brings up a fundamental distinction between knowledge storage and knowledge retrieval. Storage is about accumulating information, while retrieval is about quickly accessing and using the correct information at the right time. It requires digestion.

It’s kind of like Amazon. Amazon has made buying books and getting them on my shelves easier than ever. I’ve got 1000s of books with answers to many of life’s questions. But, I’d estimate that I’ve really only read around half of the books I currently have on my shelf. The point is that having a book on your shelf with the answer to a problem is not the same as having the answers.

I now have many thousands of articles in my Evernote. There are probably over a hundred of them about better “prompt engineering” or using “prompting techniques better”... but I can’t pretend that each article has made me better at those things. I have gotten better at thin-slicing and knowing what I want to store to improve the quality of the raw material I search for.

So now, I’m exploring how to maintain a balance. I still want to leverage AI’s value, while reintroducing a layer of slowness and reflection into the process. Maybe that means manually summarizing some articles. Maybe it means pausing to journal about what I’ve read, or discussing it with someone. The goal is not to abandon the efficiency — but to ensure that efficiency doesn’t come at the cost of depth.

The priority is making sure I’m optimizing on the right thing. It’s not progress if you’re taking steps in the wrong direction.

Let me know what you think about that ... or what you are doing that you think is worth sharing.

Onwards!

Posted at 08:20 PM in Business, Current Affairs, Gadgets, Ideas, Market Commentary, Personal Development, Science, Trading, Trading Tools, Web/Tech | Permalink | Comments (0)

Make Way For 2025's Biggest Unicorns

Billion-dollar startups are becoming increasingly common with VC funding surging, and an increased focus on exponential technologies.

VisualCapitalist put together an infographic based on May's PitchBook that highlights the newest Unicorns.

If you are curious, PitchBook defines Unicorns as venture-backed companies valued at $1 billion or more after a funding round, until they go public, get acquired, or drop below that valuation.

Here is the list for 2025.

Pitchbook via visualcapitalist

Topping the list (and eclipsing every other company on the list) is Yangtze Memory out of China. They're focused on flash memory and solid-state drives. Yup, that's still a thing.

Also high on the list is Abridge, an American AI startup focused on turning doctors' conversations with patients into documentation. If you've ever talked with a clinician of any sort, you know how time-consuming documentation currently is. The combination of AI and longevity—or age reversal—is likely to become an increasingly hot area for investment.

Meanwhile, a rising tide floats many boats ... and with the continuing rise of funding in AI, you'll also find a growing list of AI unicorns, like Peregrine, Synthesia, AnySphere, Mercor, and The Bot Company.

Although these individual companies are interesting, the larger trend is probably more significant.

There have been 43 new unicorns in 2025 alone. And while the most profitable unicorns from 2024 are still OpenAI, ByteDance, and SpaceX, their competition is on the rise.

I've been a tech entrepreneur for decades, so I'm used to the constant march of progress. But this feels different. The pace is quickening!

We certainly live in interesting times!

Posted at 11:02 PM in Business, Current Affairs, Gadgets, Ideas, Market Commentary, Science, Trading, Web/Tech | Permalink | Comments (0)

Reblog (0)