A few years ago, I shared a presentation called Mindset Matters that I had given to a small mastermind group.

This past week, I briefly revisited that content in a different group. It reminded me that some ideas are “Timeless” and worth revisiting.

So, my hope is that this post sparks some interesting ideas and discussions.

Energy Is One of the Most Important Things to Measure.

One of my core beliefs is that energy is one of the most important things we can measure.

I believe it so strongly I paid Gaping Void to put it on my wall.

via GapingVoid

It means exactly what it sounds like – but probably also a lot more than that.

On a personal level, energy affects how you feel, what you focus on (and what you make that mean), and, consequently, what you choose to do. That means it is a great way to measure your values, too.

On a business level, energy impacts more than you might recognize. It has a lot to do with who you hire and fire, where you spend your time, the target markets or segments you pursue, and even your company’s long-term vision.

Ultimately, if something brings profit and energy, it is probably worth pursuing.

In contrast, fighting your energy is one of the quickest ways to burn out. Figuring out who and what to say “no” to is crucial to estaying on track and reachingyour goals. This is where mindset and mindset scales apply.

Mindset Matters.

Watch this short video on Mindset Scales. It’s packed with insights and tools you can use as targets and filters.

Subscribe to Howard Getson’s YouTube Channel

The video highlights the critical role that specific values and mindsets play in business success. It goes over a few easy exercises (including how to create a Mindset Scale) to help identify and assess the path to desired outcomes.

One of the techniques I’ve developed is called the “Three Word Strategy”. It’s based on the idea that people, capabilities, products, and even companies can be described in a three-word strategy (think of it as a “recipe for success”). By understanding this process, you not only can help choose the right people, but it might also help to create the right technology to achieve that (think of this as a digital WHO to do the HOW) in a way that helps and supports the humans involved in the process.

Three-Word Strategies.

I believe that words have power. Specifically, the words you use to describe your identity and your priorities change your reality.

First, some background. Your Roles and Goals are nouns. That means “a person, place, or thing.” Let’s examine some sample roles (like father, entrepreneur, visionary, etc.) and goals (like amplified intelligence, autonomous platform, and sustainable edge). As expected, they are all nouns.

Next, we’ll examine your default strategies. You use these to create or be the things you want. The strategies you use are verbs. That means they define an action you take. Action words include: connect, communicate, contribute, collaborate, protect, serve, evaluate, curate, share … and love. On the other end of the spectrum, you could complain, retreat, blame, or block.

People have habitual strategies. I often say happy people find ways to be happy – while frustrated people find ways to be frustrated. This is true for many things.

Seen a different way, people expect and trust that you will act according to how they perceive you.

Meanwhile, you are the most important perceiver. Think about that for a moment!

Another distinction worth making is that the nouns and verbs we use range from timely to timeless. Timely words relate to what you are doing now. Timeless words are chunked higher and relate to what you have done, what you are doing, and what you will do.

The trick is to chunk high enough to focus on words that link your timeless Roles, Goals, and Strategies. When done right, you know that these are a part of what makes you … “You”.

My favorite way to do this is through three-word strategies.

These work for your business, priorities, identity, and more.

I’ll introduce the idea to you by sharing my own to start.

Understand. Challenge. Transform.

The actual words are less important than what they mean to me.

What’s also important is that not only do these words mean something to me, but I’ve put them in a specific order, and I’ve made these words “commands” in my life. They’re specific, measurable, and actionable. They remind me what to do. They give me direction. And, together, they are a strategy (or process) that creates a reliable result.

First, I understand, because I want to make sure I consider the big picture and the possible paths from where I am to the bigger future possibility that I want. Then, I challenge situations, people, norms, and more. I don’t challenge to tear down. I challenge to find strengths … to figure out what to trust and rely upon. Finally, I transform things to make them better. Insanity is doing what you always do and expecting a different result. This is about finding where small shifts create massive consequences. It is about committing to the result rather than how we have done things till now.

If I challenged before I knew the situation, or I tried to transform something without properly doing my research, I’d risk causing more damage than good.

Likewise, imagine the life of someone who protects, serves, and loves. Compare that to the life of someone who loves, serves, and protects. The order matters!

One more, just to get you thinking about it ... Connect, Engage, Contribute!

There is an art and a science to it. But it starts by taking the first step.

Try to find your three words.

Once you do, remember to use them. Over time, I’ve set daily alarms on my phone to remind me of them. I use them when I’m in meetings (to help orient, reflect, or inspire), and I often use them to evaluate whether I’m showing up as my best self.

You can also create three words that are different for the different hats you wear, the products in your business, or how your team collaborates.

Finding Your Three Words

Everyone feels a range of emotions. It helps if you can express them. This emotional word wheel might help. It isn’t exhaustive ... but it should give you some ideas.

via FlowingData

Like recipes, these three-word strategies have ingredients, orders, and intensities. As you use your words more, the intensities might change. For example, when my son was just getting out of college, one of his words was contented because he was focused on all the things he missed from college - instead of being appreciative of the things he had. Later, his words switched to grateful and then loving. These evolutions coincided with his personal journey ... and represented his ability and desire to take stronger actions.

Realize that we create what we want by doing. As such, choose words that inform or spark the right actions. You can see that in my son’s words. As he grew, he became more comfortable actively prompting the actions he wanted to approach life with instead of just passively hoping for a feeling.

You can apply these simple three-word strategies almost everywhere once you learn how to create them.

It’s your life. It’s your choice.

What are your words?

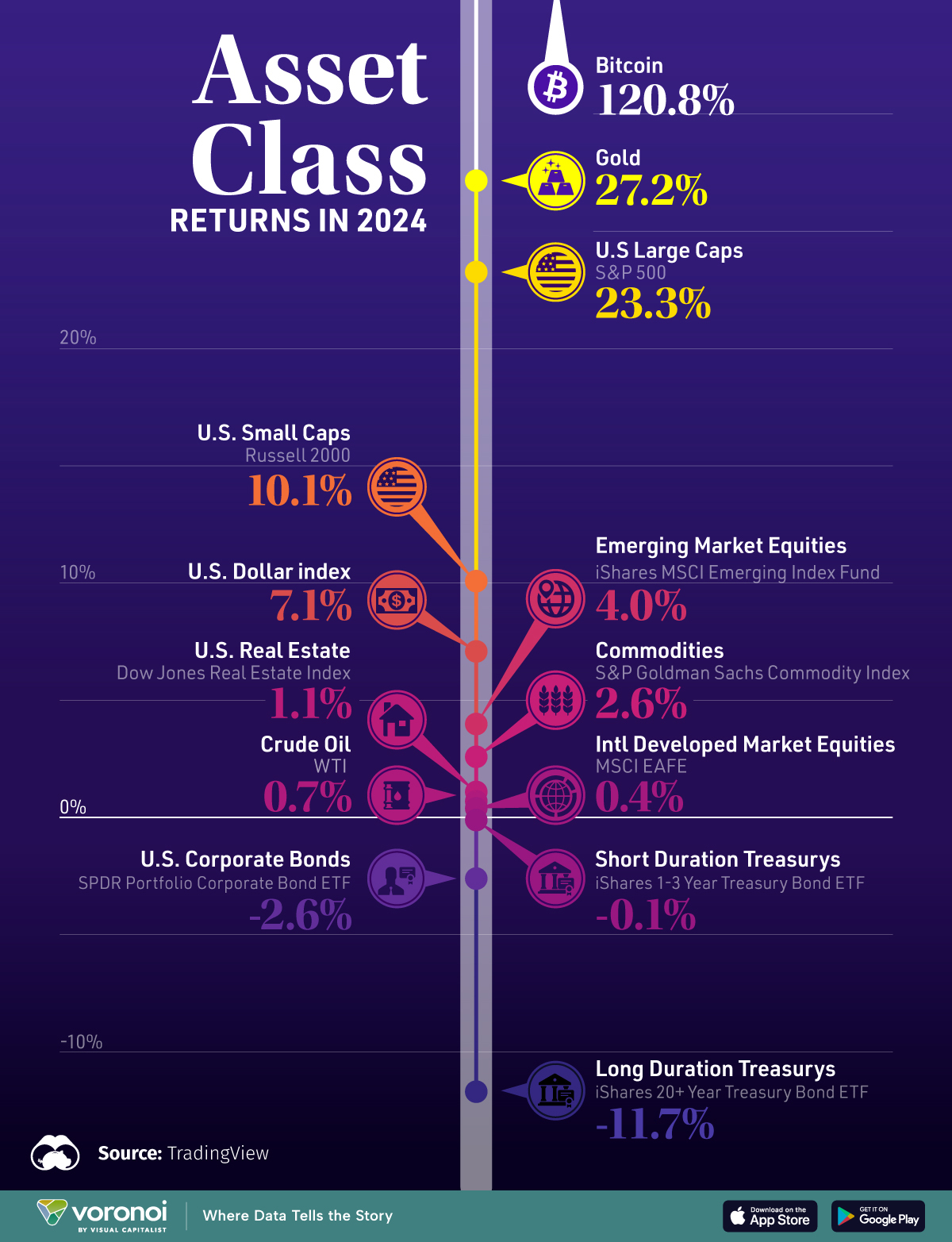

Investment in AI is Rising ...

It’s no surprise that capital raising is moving toward AI - and often generative AI.

via visualcapitalist

From 2023-2024, over $26 billion flowed into the sector - including big deals like Inflection, xAI, and Anthropic.

While many of the biggest investments were in foundational models and infrastructure, some money is now moving into targeted AI applications.

AI isn’t just for researchers and the tech giants anymore ... it’s becoming more commercial.

Realistically, AI is overhyped – and there is a lot of competition. Yet, few firms have operationalized AI in a meaningful way.

With that said, here is a question worth considering.

Where are the AI applications capable of generating returns that justify the infrastructure, investment, and focus?

The next battle will likely be in the AI Applications space. To keep it short, why hasn’t it happened yet ... and what will likely create the value we’re looking for?

Why Haven’t AI Apps Taken Off Yet?

• Cost vs. Value Gap: Many AI applications are still experimental or add only incremental value.

• Compute Bottlenecks: AI compute costs remain expensive, limiting broader adoption.

• Enterprise Hesitation: Many companies are still figuring out how to integrate AI into their operations in a way that delivers real ROI.

Where Might the Value Come From?

For AI investments to pay off, applications must solve big problems, not just serve as experimental tools. The highest-value areas likely include:

• AI copilots and automation (Enterprise AI reducing labor costs and bottlenecks)

• Autonomous systems (AI for analytics, compliance, and logistics)

• AI-driven discovery (Accelerating breakthroughs in capabilities and performance)

• Next-gen digital assistants (LLMs with memory, context, and long-term utility)

Right now, AI apps are where mobile apps were in 2008 — there is plenty of potential, but only a handful of genuinely indispensable use cases.

Companies like Capitalogix that crack the code on industrial-grade AI applications, will drive the next wave of value creation.

It’s fun and rewarding to watch artificial intelligence become available to everyone.

As the cost of “intelligence” decreases, let’s hope more people take advantage of the opportunity.

However, the sad truth is the opposite is also more likely. As AI becomes more available, it becomes easier for it to become a distraction.

Remember the Internet? When it first started, most of the uses were academic. Now, despite there being functionally infinite ways to use the internet to improve your life and make you smarter, most people use it for memes and distractions.

When you think about AI, don’t just think about artificial intelligence ... Think about amplified intelligence. That is the term I use to distinguish between the technology and what people really want ... which is the ability to make better decisions, take smarter actions, and continuously improve performance.

AI isn’t about taking away the humanity from your business or automating away the things you love. It’s about allowing you to be more human – doing more of the things you’re best at - that give you energy and bring you joy.

Posted at 08:08 PM in Business, Current Affairs, Gadgets, Healthy Lifestyle, Ideas, Market Commentary, Personal Development, Science, Trading, Trading Tools, Web/Tech | Permalink | Comments (0)

Reblog (0)