The recent shutdown has brought light to the disparity between markets and economics, and also served to widen the relationship.

In high school, most of us were taught basic supply and demand. Some probably took a macroeconomics course, fewer got an MBA, and I know some of you reading this are actual economists or traders.

Yet, most people (even some economists) misunderstand what drives financial markets.

In theory, share price is supposed to be the net present value of the future earnings stream. This is a "weighing" mechanism that also balances positives and negatives, short-term and long-term issues, industry cycles, fundamental data, and a host of other issues.

The markets represented the collective fear and greed of a population. A trader doesn't need to guess what someone specific is going to do … their calculus is more about the law of large numbers. How will most people respond to a sudden move up or a sudden move down? Will they see it as a danger or an opportunity?

In a sense, markets operate like an actuary for an insurance company. Actuaries don't need to know when you will die, specifically, but rather if they insure 10,000 people like you, how many are likely to die this year (and what premium can they charge to cover the death benefits to be paid, the cost of operations, plus their intended profit margin.

In the basics of economics, markets and their consumers play a sort of tug-of-war until an equilibrium is set. Price represents the amount of money a consumer is willing to pay for this good (or a comparable good) and the amount of money a seller is willing to sell it for taking into account overhead, manufacturing, time-value, etc.

It's not necessarily the maximum cost a consumer would pay and minimum a seller would sell, but for the sake of this discussion, that nuance isn't overly important.

The markets were an important price discovery tool using "open outcry" as a way to see at what price others were willing to buy or sell.

As markets got faster and transactions stopped being generated solely by people trading with people, the pricing mechanism changed. I think of it as a fair value range surrounded by a fair speculation buffer. As markets get faster, noisier, and more volatile, the fair speculation range expands. That means pricing is more dynamic and edges decay faster than ever.

This also means that less of the price is based on simple things, like whether the economy is improving or declining. As we've seen, markets can soar even when economies face serious existential threats.

Market structure, today, involves many more players investing for many different reasons. Gone are the days when the market waited with bated breath for Fed conferences, earnings reports, and presidential updates. Instead, you have speculators, passive investors, fundamental investors, quantitative investors, companies trying to hedge bets, market makers, manipulative algorithms, governments, and more … all involved in trench warfare seeking an edge.

They trade for different reasons – some may make sense logically to you, others are executing part of a strategy you may never figure out. But, together, they form the engine that powers the market. Markets really are a collection of forces all focused on trading.

Simplifying, you can look at the decline in the economy compared to the relative stability of the stock market (in light of the world shutting down), as proof of this. Economic stimulus played a massive role in propping up the market, but so did the comparative variety in why market participants trade. It's why you still see liquidity in the markets despite the decrease in consumer confidence and economic activity.

Sure, the government created increased liquidity, stimulated markets, and even participated directly (and indirectly) at plunge protection. But that is the playing field all traders have to play on right now. It doesn't matter if it reflects the realities you see in the economy or the world.

Today's markets are much more complicated than before. Moreover, the vast amount of information available (whether true, false, relevant, irrelevant, clarifying, or misleading) creates a vast signal-to-noise ratio challenge. Meanwhile, many market participants (like many day-traders) have simply ridden the wave here, though it's unlikely that a vast majority of them truly understand what they're doing. Think of this as the "Smart Money" versus "Dumb Money" … and it doesn't usually end well for one of them.

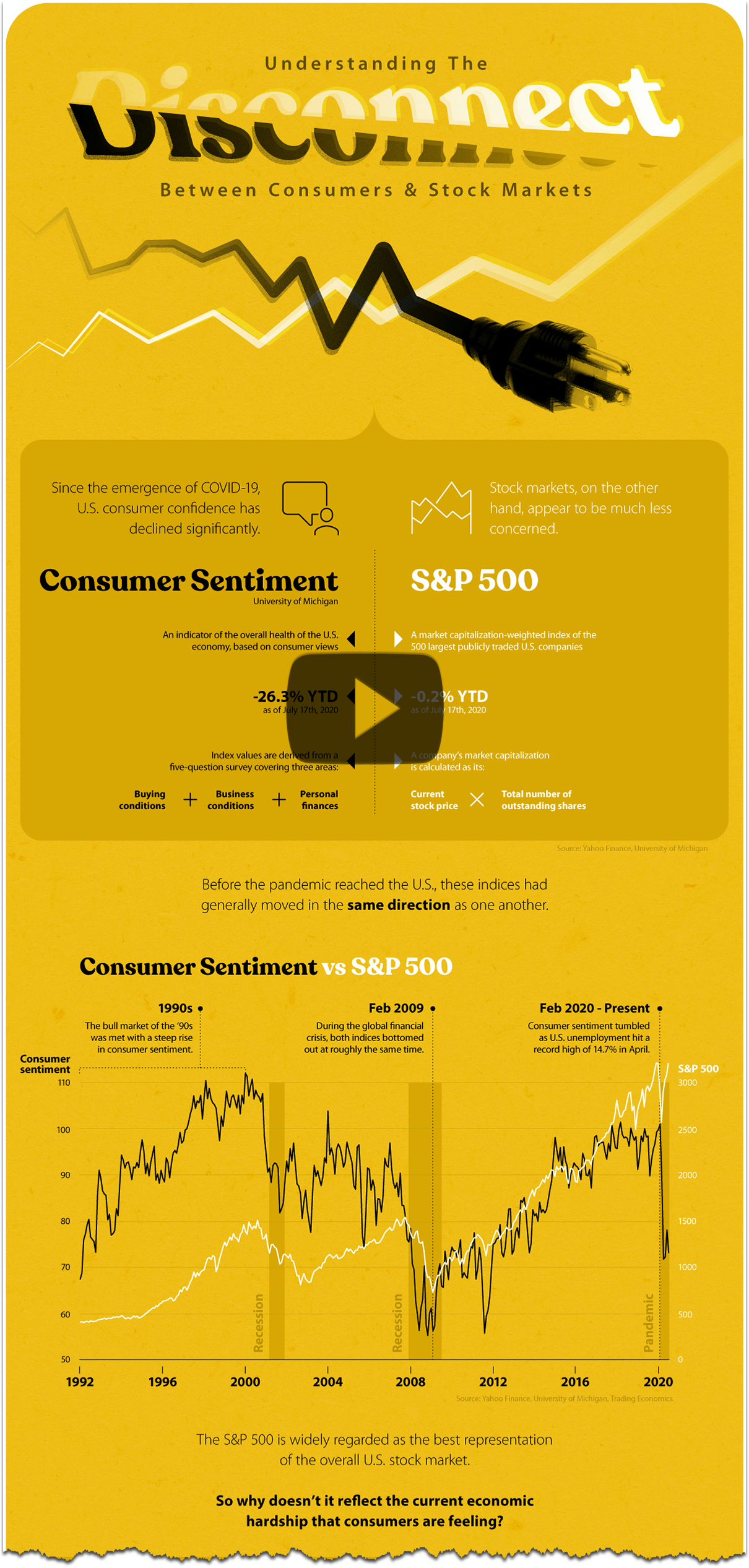

VisualCapitalist put together a great infographic looking at the difference in response to the shutdown via economic activity and the S&P 500 as of July 17th.

via visualcapitalist

via visualcapitalist

The chart makes the valid point that the S&P 500 is not an equally-weighted index and is currently driven primarily by the tech giants, even with other industries struggling.

Consumer sentiment is still a factor, and news cycles can absolutely still impact stocks, as evidenced by Kodak's meteoric growth (and subsequent decline) last week.

All-in-all, there are lots of things influencing markets besides the economy. It is a lot to take in (especially for us humans who can only process seven things plus or minus two at any one time.

It is no wonder that Smart Money is relying more on exponential technologies (like AI and Big Data).

Be safe!

Onwards!

Leave a Reply