Recently, Ray Dalio released a letter "Why and How Capitalism Needs To Be Reformed, Parts 1 and 2."

I believe that all good things taken to an extreme can be self-destructive and that everything must evolve or die. This is now true for capitalism. In this report I show why I believe that capitalism is now not working for the majority of Americans, I diagnose why it is producing these inadequate results, and I offer some suggestions for what can be done to reform it.

In it, he outlines what he thinks the problem with our current capitalist system is, and offers some solutions. My friend and great economist, John Mauldin entered into a fun dialogue with Ray about where they agreed and disagreed.

Before anyone gets up in arms without even having read their treatises, both are staunch capitalists and believe strongly in America and Capitalism.

Fundamentally, they shared a lot of opinions, but some key differences in takeaways, specifically around Modern Monetary Theory. They agree that the existing system isn't producing equal opportunity and that equal opportunity is an important aspect of capitalism. Here's their discussion if you want to do your full due diligence.

- It's Time To Look More Carefully at "Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)" and "Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)" – Ray Dalio

- Ray Dalio Is Kinda, Sorta, Really Wrong – John Mauldin

- Clarifying What John Mauldin And I Agree And Disagree On About How Capitalism Is Working – Ray Dalio

Instead of trying to fully encompass and summarize their bodies of work, I encourage you to do your own research.

I am, however, sharing a response written by our CIO, John DeTore. I first met John DeTore and John Mauldin at Camp Kotok, which I've written about many times.

I am, however, sharing a response written by our CIO, John DeTore. I first met John DeTore and John Mauldin at Camp Kotok, which I've written about many times.

Last year, I brought John DeTore in to talk to my data science team and put them through the wringer. He had years of experience at several large firms and taught Active Management at MIT. He was scheduled for two hours. He stayed for eight. He was impressed by what we'd accomplished with a pure data science background and was excited to add his quantitative expertise. I knew I needed him on the team, and the rest is history.

Here's his full response to Ray and John on their takeaways and the idea that "this time it's different":

___________

Dear John,

The latest writings you have produced have been fun and illuminating … some of the most hard-hitting economic analysis I’ve read lately. The back and forth with Ray Dalio effective and entertaining! I appreciate that you are not just discussing what has been happening, and why you think it’s happening, but what we should do about it.

Thesis:

As seasoned observers, I think you both would agree that “this time it's different” is a phrase to use with caution. We have all seen this expression invoked … just to be proven wrong. We need to be judicious in our observation of phenomenon that means that the “usual order” needs to change. This is the exception, not the rule.

I believe, however, that there are significant structural issues that are different this time … and that it is important to deal with these issues to get to effective policy to properly respond to our current economic situation.

In brief: 1) The Fed is lost as to why they don’t need to tighten. Tightening is a crude and imperfect, and possibly dangerous, way to slow the economy when inflation is a threat. Inflation is not a threat. 2) Long rates are too low. (This leads to the conclusion that the federal debt must not be that much of a problem.) So Dalio’s QT3 is not to be feared … and is probably needed. Somewhat higher long rates might be a good thing. 3) If we want the strong economy and just freedom that capitalism can bring, we need to fear structural issues that threaten good capitalism. The enemy is concentration: too few people with power, too many monopolies and too little intervention to keep capitalism working. Big Technology, Big Finance, and Big Pharma come to mind.

Discussion:

The supply-side shock

In the first year of the current administration, we enacted a huge change in the corporate tax rate and enacted sweeping change to regulatory burden. This represents a significant supply side shock. (Typically, I believe we ascribe too much importance to the effect White House policy has on the economy. I mean, the economy is big and diverse, and most administrations bogged down in grid-locked political administration. This time might just be different.)

As I remember from college economics, this pushes the supply curve out while leaving the demand curve untouched. The effect is to increase output and decrease prices. I believe that we are in the midst of this big shock with its impact on both output and prices. (It is as if the classic lemonade stand one day learned how to make the same glass of lemonade that cost $0.25 for a cost of $0.05. One way or the other, we will end up with more lemonade at lower prices.) At the aggregate level we end up with GDP growth and disinflationary forces.

Corporations, due to significantly lower taxes, have more to spend on operations, and are free to both invest and compete for scarce labor and bid up wages. This is OK … it was overdue and can be somewhat offset by the disinflationary impact of the supply shock. It isn’t inflationary if stimulated by a supply-side shock.

This produces the wonderful holy grail: more output, price stability and growing wages inside that price stability. How confusing this must be for the Fed! We make both of their objectives easy for them, then ask what policy changes they need to make. (Of course, there is little for them to do except enjoy their good fortune!!)

In particular, we should not misunderstand the Phillips curve … even Alban Phillips agreed the curve moves all the time. (It represents only the current, short-term trade-off between wage inflation and unemployment. But since it moves all the time, it is not a good forecasting tool for wage inflation — or inflation in general). Often, I think the Fed believes low unemployment portends general inflation in the near future. This is not a good conclusion today … perhaps why we keep waiting for inflation that doesn’t materialize.

Where is all the employment coming from??

It is fair to ask how we can be at full employment yet growing monthly employment at numbers greater than 200K a month. If we are essentially out of unemployed people, where are all the jobs coming from?

The question is an important one. If we are out of people, we are due for an accelerating labor shortage and possible inflation and growth limits. If not, labor will not be a limiting factor anytime soon.

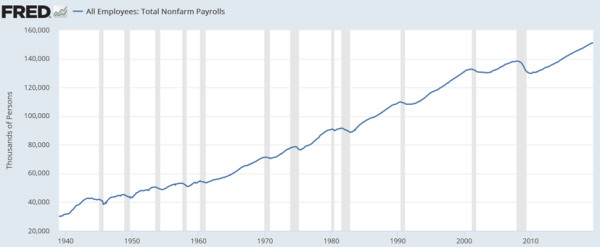

To me the ingredients of macro growth are 1) labor, 2) capital and 3) animal spirits. With rates this low, and the enthusiasm of the policies of the current administration, we have 2 & 3 in bountiful supply. But with regards to labor, consider long-term payrolls in the US economy:

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED

The point of this chart: the total employment we lost in the 2008 crisis has never been made up. The green line helps see that this crisis was quite different with its permanent destruction of jobs. We permanently wrote off what appeared to be almost 10M people. Some of these are lost to retirement as the baby-boomers are approaching that age, but it’s possible there are many people who can still return to the economy … and others that can upgrade their position. Part of the strength we see now may be the final recovery from the financial crisis … delayed in part through the policies of the last administration and other issues that left corporate management with more pessimism than would normally be seen in a recovery.

High Federal Debt

Our debt binge started with a gambit by George W. gone bad: reduce gov’t revenue and eventually spending will be reduced to match it. This didn’t happen of course, and the Federal debt accelerated. Bring on an economic collapse in 2008, and we doubled down with a Keynesian debt expansion to aid the recovery. Of course, to be Keynesian about it, we should have run a surplus as the danger of economic collapse passed. What to make of our runaway debt today?

John, one lunch at Ocean Prime we went over the absurdity that QE3, in fact, essentially monetized a chunk of this debt. To me, admitting that QE3 was monetization is step one of understanding the issue. (I wonder if it was a test run for Dalio’s MP3.) How could we have monetized $4T of government debt — and see interest rates fall? Shouldn’t our rates accelerate? Our currency fall?

In part, we might argue governments all over the world are doing this, so as all our currencies fall together, we don’t notice movement in exchange rates. If this is true, gold would be rising rapidly and to some extent this has been true recently. But a significant percentage of OECD debt is now at negative rates. We can make no other conclusion that investors desire government debt, and capital is very cheap and available — perhaps more now than ever.

Perhaps the experiment of QE3 should be repeated, at least as long as the markets do not punish us. Has the Fed continued to buy up long-dated treasuries? Call the bonds from the Fed and pay for them with IOUs of some sort. The IOUs will revert to the treasury where they will be shredded. Voila! Debt is gone. Last year I spent hours discussing this at Camp Kotok with people who should know Fed accounting and methods better than anyone. I got no pushback. In fact, this is on Dalio’s table of example MP3.

Of course, were this to work, we need not go through with it. We only need to acknowledge that the debt is not a problem. In fact, that is what the current low rates are telling us right now — no sovereign risk for OECD.

The role of long rates

To me, one key role of long rates is to set a fair price between borrowers and lenders. For instance, it's common for retirees to hold bonds for income, and for young families to borrow long-term through mortgages to purchase houses. Though there are of course intermediaries, I find it helpful to see long rates as an inter-generational negotiation. Long rates govern retirement rates of return, pension liability calculations, and mortgage rates (which drive housing prices).

Typically, these rates are set through the invisible hand, but what happens when the government intervenes and lowers long-rates artificially:

- Mortgages become artificially too low, perhaps driving housing prices too high (we are not subsidizing young families, we are having them incur more debt when buying their homes from long-term owners).

- Pension liability calculations are too high, causing significant funding shortfalls. Yes, too low long rates are one culprit to the underfunding problem.

- Corporate bond yields are too low, boosting EPS, but also leading to potentially aggressive spending decisions.

- Particularly weak companies hang on instead of folding (“zombie companies”).

- Retirees who desire the financial stability of liability immunization find that even significant savings produce a surprisingly small income. Millionaire retirees might not even have the income of the maid that helps them in old age.

My point is not to argue about all these policies. It is only to say that pushing rates away from the natural equilibrium to stimulate the economy can unfortunately also have some serious side effects. At a minimum, it distorts housing prices and retirement programs in significant ways. It is not hard to surmise that these inefficiencies might slow the economy in some way — counteracting the simplistic notion that artificially low long rates stimulate the economy.

Income inequality

We hear a lot of discussion about social unrest coming due to a supposed unjustly large spread in incomes.

Some economists attribute this, to some degree, to easy Fed policy. It stimulates big business and tends to inflate asset prices, both of which could be argued to most benefit those at the top. I’d just like to point out that many people have done versions of the long-term inequality graph and credible efforts look particularly like income concentration is inversely correlated to interest rates. These graphs all show that the most “equal” time coincides with interest rate peaks in 1980. Most of the most inflaming graphs depicting growing inequity start in 1980 — those with a long-term perspective show the level of equality now approaching pre-WWII levels.

If solving “income equality” requires returning to late 70’s macroeconomic conditions, I am not in favor.

For the moment, I’d like to suggest another culprit for the disruption of our income distribution harmony… There is a peculiar fall-off in the number of listed companies in the US:

The Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks via Credit Suisse

This trend started in the late ’90s and could potentially be caused by a number of factors, and it could result in a number of impacts. The phenomenon is under-researched, but the papers that have been done look at issues like 1) impact of Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX), 2) growth of private equity capital, 3) the growth of M&A activity on Wall St and its need to keep the pipeline growing, and 4) a number of structural issues (like SOX) hurting small company formation.

While it is tempting to immediately blame SOX, the research I have seen seems to support that the larger impact is a birth of large pools of private equity capital, the resultant fueling of corporate shopping through increased M&A activity, and the simultaneous birth of alternatives to the IPO. In summary: as we have chosen to allocate institutional assets away from public stocks and towards private equity, the M&A industry has provided means.

Of course, this could have a number of impacts. It's reasonable to think that it drives inequity. I think it could drive other things, many of which are counter to the free market capitalistic society.

As our corporate base consolidates, we concentrate more power in fewer management teams … and fewer CEOs. We likewise have fewer CFOs and COOs, but those that remain might earn particularly high incomes, or may benefit from the M&A spoils to pad their wealth. It's easy to see how this causes income inequality, specifically in corporate senior management.

But consolidation means fewer payroll departments, more consolidation in rank and file operations, and less breadth of competitors. All of these may have an effect on our economy.

When I was a child, but old enough to ask, my parents explained competition to me. They said any industry requires several companies in it, and if too much consolidation occurs the Department of Commerce steps in. (They also said it was quite illegal to charge different process to different customers.) Capitalism works, but over-consolidation leads to monopoly or oligopoly profits.

The current political debate over capitalism is wrong-headed. We need to reacquaint ourselves with its principles … pay more attention to keeping markets free and agile. Consolidation in tech companies, banking and healthcare have yielded industries that are too profitable, and the elite leaders of these organizations (Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Goldman Sachs, other large banks, the large drug companies) with paychecks that drive the “income inequality” statistics. Sure, the top 10% is doing well, but careful analysis will show this is almost entirely driven by how well the top 1% are doing. (John, you showed this chart, but I am choosing a graph that adds the 5% and 10% curve for comparison.)

Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States by Emmanuel Saez

Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States by Emmanuel Saez

Rockefeller, JP Morgan, Zuckerberg, Bezos. They represent their eras, and each provided great insight and value to the American economy. But it’s hard to argue that they do not benefit from some degree of monopoly profits.

Conclusion

This time it is different:

- Conventionally, we expect that such low rates of unemployment should cause wage inflation, but that isn’t happening

- Conventionally, we believe unprecedented levels of government debt will create problems for markets, or at least higher rates, but that isn’t happening

There seems to be an economic quagmire: we worry about inflation acceleration; long rates keep falling. The Fed pushes short rates up, but even at full employment or beyond, we have trouble observing anything that looks like persistent inflation.

Time to at least consider:

Inflation is not going to be a problem:

- There may still be many people to join the workforce

- Structural, and very positive, supply-side shocks are working their way through the system

(Long rates seem to confirm that inflation is not a problem)

US Government debt is not a particular problem:

- I’d prefer a Dalio style MP3 that exchanges higher long rates for lower government debt, if only to correct the inefficiency of long rates that are too low (below where the invisible hand would set them)

- The real goal should be to return control of long rates to the invisible hand.

(Again, long rates seem to confirm that debt isn’t a problem)

We do have macroeconomic issues to deal with. These are the real issues, not those above:

- There is a concentration & consolidation of our important growth industries: tech, finance and healthcare

- Additionally, finance has been targeted for significant regulatory help that benefitted large firms over small ones

- The massive funding of private equity pools, and the resulting ramping of a significant M&A business on Wall St. has concentrated power in the hands of too few. We have massively overdone mergers. This not only adds to inequality … it imperils the agility and growth of the economy.

- This results in:

- very high profitability of winning large companies

- possible sidelining of a good number of our most talented senior executives at the prime of their life

- a reduction in the number of companies

- a reduction in small companies hurts one of the most vibrant sectors for innovation and job growth

- this concentration also manifests as some of the drivers for income inequality

- We need to consider

- increasing Commerce department vigor towards any monopoly

- a national healthcare policy that restores basic competition to the industry

- regulatory or tax changes that incent IPOs over mergers, and/or spinoffs over mergers.

A sign that policy is working here: IPOs, spinoffs, large breakups, and eventually a return to trend number of public companies.

__________________________

There's a lot to discuss when it comes to our US and global economics. While I expound the inefficiency of economics as a driver of trading decisions, it plays a huge role in the daily and professional life of every one of us.

Let us know what you think.