While space and space travel aren’t our usual topics of conversation, they do come up frequently.

When you think about the future of technology, it‘s not just AI, automation, and Ozempic. Two emerging frontiers we don’t talk about enough are healthcare (longevity, regenerative medicine, and other breakthroughs) — and, you guessed it, Space.

Space Still Feels Like the Final Frontier

Growing up in the 60s and 70s, Space was a bastion of technological advancement, and it captured the collective minds of America and the World.

I still remember watching the lunar landing and thinking how cool it was (and it still is)! And as a strange coincidence, over the past week, I’ve had three separate people comment that it was staged and fake (but that’s a totally different story, and I’m not going to write about it).

Then, for decades, space exploration faded into the background. The zeitgeist moved on. It wasn’t until Elon Musk and SpaceX brought it back into the limelight with grandiose claims that we started to see meaningful momentum.

Don’t get me wrong, the wheels were still turning behind the scenes, but it’s amazing what focused attention can do for an industry.

- In 2018, Elon launched his Tesla Roadster into Space. It was clever marketing—rand a major step toward cheaper space travel and large-scale private investment in the Final Frontier.

- In 2020, SpaceX teamed up with NASA to launch a historic spaceflight, the first time a private vehicle carried astronauts into orbit to the ISS.

- By 2021, more than 10,000 space industry companies existed worldwide, and total investment had passed 4 trillion dollars for the first time.

- In 2024, 51 years after we first landed on the moon, the U.S. made it back, led by the private company Intuitive Machines.

We’ve evolved from government showpieces to a commercial ecosystem

Humanity’s Future in Space

I love spaceflight for many of the same reasons I love AI.

It’s a global initiative heralding innovation and improvements that promise to transform the world (or worlds). It is a catalyst for many exponential technologies. And in many respects, it is the path to our inevitable future.

Many astronauts, even from the Apollo era, talk about the incredible feeling they experience after a few days in Space. As they look at Earth from above, they lose their sense of borders and nationality. They call it the “Overview Effect”. The Saudi astronaut Sultan bin Salman Al-Saud, who flew on the Space Shuttle in 1985, commented on this, saying, “The first day or so, we all pointed to our countries. On the third or fourth day, we were pointing to our continents. By the fifth day, we were aware of only one Earth.”

On some level, space changes how we see borders, conflict, and collaboration.

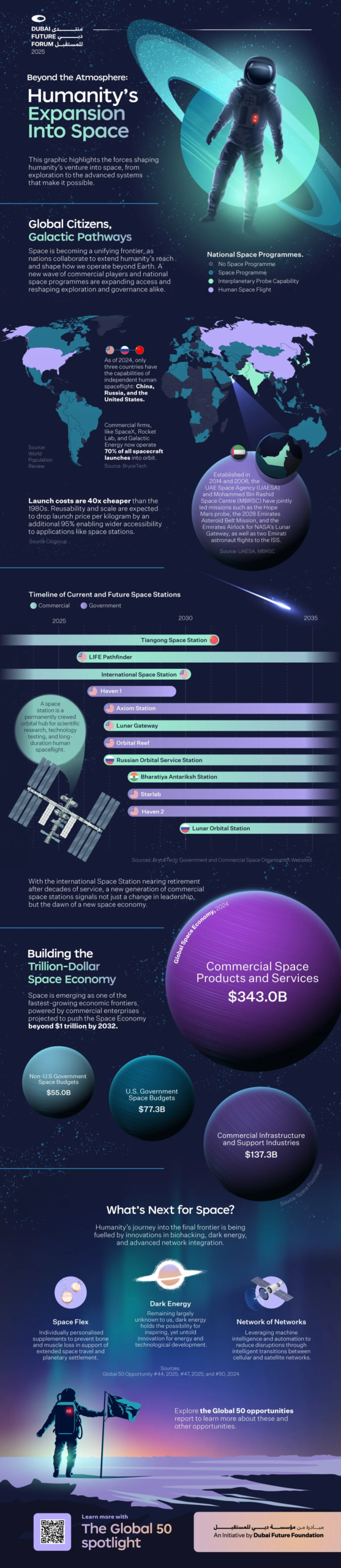

The infographic below comes from the Global 50 Future Opportunities Report from the Dubai Future Foundation. It introduces the breadth of programs and capabilities enabling humanity’s expansion into Space.

via visualcapitalist

While only three countries currently have the capabilities of independent human spaceflight (China, Russia, and the United States), eight countries now have interplanetary probe capabilities.

Today, commercial firms conduct about 70% of all spacecraft launches, and launch costs are 40 times lower than in the 1980s.

What Comes Next?

As the ISS nears retirement, the future is far more commercial, with several private stations planned for launch from America, such as Axiom Station and Haven-1.

What excites me most now are the innovations enabling the next wave of exploration — and it’s not just cheaper space travel.

- Space Flex – biohacking at the next level offers personalized supplements to prevent bone and muscle loss, supporting longer space missions and eventually planetary settlement.

- Breakthrough Energy Sources and Storage – Breakthroughs in areas like cold fusion, energy storage, and dark energy are vital to powering advanced spacecraft and sustaining long-term settlements.

- Network of Networks – advanced AI, automation, and communication networks will reduce disruptions and enable intelligent transitions between satellite and cellular networks. This is important for resilient connectivity in autonomous systems and disaster response.

For investors and innovators, Space is less about rockets and more about a platform for new industries: in‑orbit manufacturing, earth observation data, resilient communications, and even biomedical breakthroughs unlocked by microgravity.

When you zoom out, the “space age” is really an extension of the digital and AI revolutions into a new domain — one that will reshape risk, opportunity, and how we think about growth timelines.

The Power of the Space Race

For the first time, it feels like we are not just visiting Space; we are building there.

Stations, networks, and new technologies are laying the groundwork for a permanent presence beyond Earth.

Humans are wired to think linearly and locally, but I am grateful that some people see farther. While the universe is vast beyond comprehension, so is human curiosity. And as technology grows, so does our reach … and the questions we can afford to ask.

Every new step outward expands what we believe is possible.

We are only beginning to build the infrastructure of the space age, and the most exciting chapters are still ahead.

In an era of intense global political strife, it gives me hope to see an initiative that links and aligns so many powerful minds.

Onwards!