I'm launching a new newsletter - with a twist. The newsletter will be fully automated and produced by an AI we are training to pick out the articles to highlight and share.

Don't Let the Past Get In the Way of the New.

Even though a lot of what I think and write about is innovation, exponential technologies, and automation ... until now, what we write and send has been the result of human effort rather than artificial intelligence or technology.

Sure, portions of the process leverage technology ... but humans have written the vast majority of what you read here.

It takes many hours a week. Frankly, many more hours than you would guess!

Still, I enjoy working on the Weekly Commentary and the list of links that I share. It is a labor of love (or OCD?) that I have been producing for about twenty years!

If you aren't a subscriber yet, please click here to get it!

We currently send out two weekly e-mails. The one that comes out on Fridays is a hand-curated list of links that I found interesting during the week. The Sunday edition has two articles written by me and my son, Zach, along with a few more links.

Deep down, I know that AI is now good enough to curate a high-quality list of articles in a more efficient, effective, and certain way than what I produce.

So, we are about a week away from launching this.

This is my John Henry Versus The Machine.

And I'll tell you what – I'm worried.

The new AI-generated newsletter is really good.

Why Play a Losing Game?

I know that I will lose ... But I also know that I will win. And so will you!

This does not have to be an "either-or" decision. This is a "both-and" decision. Meaning ... I don't have to decide whether to stop producing by hand, in order to also produce with AI.

One of the challenges with AI is that the fitness function you choose significantly impacts the result you achieve.

If the purpose of the newsletter was only to produce a quality newsletter in less time, with less effort, and with greater certainty that readers engage ... then the result is inevitable. The AI newsletter wins.

However, I didn't choose to produce the newsletter for the newsletter. The newsletter is a natural result of my nature. I did the research because I wanted to do the research.

I am naturally curious and passionate about these things. It's what I think about. It's who I am ... and what I do.

The Weekly Commentary and Link List are strategic byproducts of something that I'm going to choose to do anyway,

AI Won't Replace the Real Magic.

One of my beliefs about AI is that you shouldn't use it to replace your Unique Ability. In other words, don't try to automate, delegate, or outsource something you are great at, if it gives you energy. The goal is to magnify "magic," not replace it. The goal is to spotlight and support those areas by taking away things that are frustrating, bothersome, distracting, or taking cycles away from something that would produce a greater result with less energy.

The point is, I can do both. I will still do research because it gives me pleasure, knowledge, and a greater likelihood of continuing to learn and grow. I will continue to write and curate.

Why? Because it's also an important part of my thinking process. I think when I speak. I think when I write. But more importantly, I think when I am preparing to speak or write. I wouldn't be me if I didn't go through that process. I also don't believe my ideas or opinions would continue evolving without the challenge and effort.

And I will also enjoy evolving new and different channels of communication.

Hopefully, we all benefit.

So, I hope you sign up for the new newsletter. We'll be sending out the first e-mail within the next week or two.

As I've said, I love writing and researching. I'm an innovator at heart.

Many read my articles because of my commitment to AI, new technologies, and the future. Most of my exploration has been centered on Capitalogix and our Amplified Intelligence Platform. But there are a lot of exciting new use cases of AI, and I'm exploring many of those apps right now.

For example, as you could have guessed, one such use that I'm excited about is AI-curated newsletters. Many people I trust and respect have started using Daily.AI, including Peter Diamandis, Dan Sullivan, Joe Polish, and Chris Voss. It's clearly a successful modality.

A Thousand Mile Journey Starts With a Single Step.

Hopefully, you are excited about the new newsletter and the value you will get from it.

I'm confident it will only improve – because it learns from what you value.

To start, the newsletter will focus on these three topic areas:

- How to build a resilient business in a fast-changing world

- The Psychology of technology & technology addiction

- Business ethics and AI ethics in today's world.

But that is just the starting point. It is set up to consider the same type of offshoots as I normally would. So, it will remain diverse and educational.

Please sign up and let me know what you think about it.

Media Bias and You in 2023

Information is Power.

Consequently, your choice of information source heavily contributes to your perceptions, ideas, and worldview.

Coincidently, news sources are a lightning rod for vitriol and polemic.

I am still somewhat surprised by the abject hatred I hear expressed toward a particular news source by those who hold an opposing bias. This often leads to claims of fake news, delusion, and partisan press. Likewise, it is common to hear derision toward anyone who consumes that news source.

Perhaps the reality is that most sources are flawed – and the goal should simply be to find information that sucks less?

It's to the point where if you watch the news, you're misinformed, and if you don't watch the news, you're uninformed.

News sources aren't just reporting the news ... they're creating opinions and arguments that become the news. Moreover, many consumers don't care enough to think for themselves or to distinguish facts from opinions.

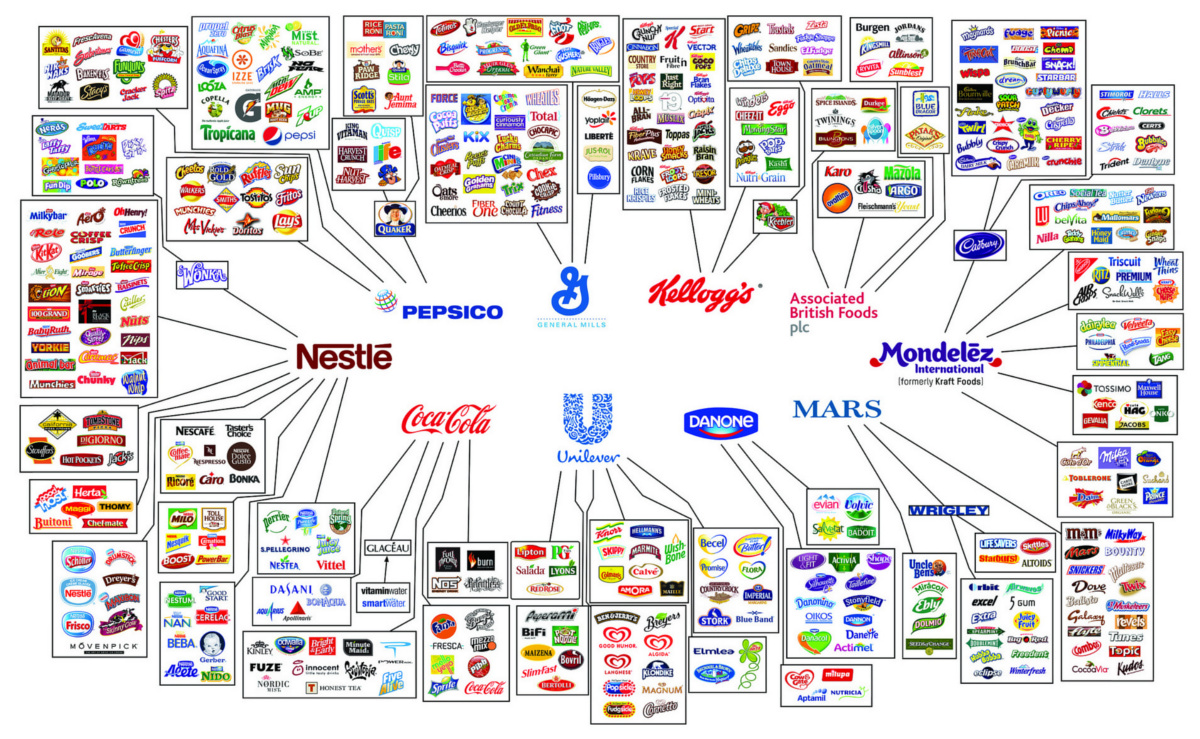

Here's a chart that shows where news sources rank on various scales. It has default options and over 1400 sources you can add to the interactive version. You can click the image to go to an interactive version with more details. It gets updated every year, and this year's just got released.

via Ad Fontes Media

I once spent fifteen minutes arguing about how you know whether the information in this chart is accurate. If you're curious about their methods, click here.

The "new normal" is to distrust news agencies, big companies, the government, and basically anyone with a particularly large reach.

Perhaps even more dangerous is the amount of fake news and haphazard research shared on social media. Willful misrepresentations of complex issues are now a "too common" communication tactic on both sides ... and the fair and unbiased consideration of issues suffers.

Social media spreads like wildfire, and the damage is done by the time it has been debunked (or proven to be an oversimplification). Once people are "convinced," it is hard to get beyond that.

In reality, things aren't as bleak as they seem. People agree on a lot more than they say they do. It is often easier to focus on "us" versus "them" rather than what we agree upon jointly. This is true on a global scale. We agree a lot. Most Democrats aren't socialists, and most Republicans aren't fascists ... and the fact that our conversation has drifted there is intellectually lazy.

This idea that either side is trying to destroy the country is clearly untrue (OK, mostly untrue). There are loonies on the fringes of any group, but the average Democrat is not that unlike the average Republican. You don't have to agree with their opinions, but you should be able to trust that they want our country to succeed.

I don't know that we have a solution. But there is one common "fake news" fallacy I want to explain at least a little.

It's called the Motte and Bailey fallacy. It's named after a style of medieval castle prioritizing military defense.

Launceston Castle via Chris Shaw, CC BY-SA 2.0

On the left is a Motte, an artificial mound often topped with a stone structure, and on the right is a Bailey, the enclosed courtyard. The Motte serves to protect not only itself but also the Bailey.

As a form of argument, an arguer conflates two positions that share similarities. One of the positions is easy to defend (the Motte), and the other is controversial (the Bailey). The arguer advances the controversial position, but when challenged, insists they're only advancing the moderate position. Upon retreating, the arguer can claim that the Bailey hasn't been refuted or that the critic is unreasonable by equating an attack on the Bailey with an attack on the Motte.

It's a common method used by newscasters, politicians, and social media posters alike. And it's easy to get caught in it if you don't do your research.

Conclusion

As a society, we're fairly vulnerable to groupthink, advertisements, and confirmation bias.

We believe what we want to believe ... so it is hard to change a belief (even in the face of contrary evidence).

But, hopefully, in learning about these fallacies, and being aware, we do better.

I will caution that blind distrust is dangerous – because it feels like critical thought without forcing you to think critically.

Distrust is good ... but too much of a good thing is bad.

Not everything is a conspiracy theory or a false flag.

Do research, give more credence to experts in a field - but don't blindly trust them either. How well do you think you're really thinking for yourself?

We live in a complicated world that is getting more complex.

Hopefully, knowing this encourages you to get outside your bubble and learn more about those with whom you disagree.

Who knows ... Something good may come from it?

Posted at 05:43 PM in Business, Current Affairs, Healthy Lifestyle, Ideas, Market Commentary, Personal Development, Science, Trading, Trading Tools, Web/Tech, Weblogs | Permalink | Comments (0)

Reblog (0)