I have a poster hanging in my office that says: “Artificial Intelligence is cool … Artificial Stupidity is scary.”

The point is that we like the idea of automation and real-time decision-making, but only if the answers are correct.

Speed amplifies truth and error. AI makes you smarter faster—or wrong at scale. Sometimes, the systems we build to make better decisions also multiply our mistakes. Several core tensions create that paradox.

- Velocity vs. Veracity: Pressure to move fast conflicts with the need to verify causal logic, not just correlation.

- Persuasion vs. Truth-Seeking: Organizations reward confidence and narrative; reality rewards calibration and evidence.

- Automation vs. Accountability: As decisions become machine-mediated, ownership blurs—who is responsible when logic fails and who is supposed to catch the error?

- Simplicity vs. Completeness: Leaders want short answers; complex realities resist neat categories and invite fallacies.

The problem isn’t just with automation. I’ve come to understand that an answer is not always THE answer. Consequently, part of a robust decision-making process is to figure out different ways of coming up with an answer … and then figuring out which of those serves your purposes best.

That distinction is essential in automation and designing agentic processes, but it’s also important to think about that as we operate on a day-to-day basis.

That’s the point of today’s post. It’s about some of the common logical errors that prevent us from getting better results.

Several times this week, I used a simple framework that says if the outcome isn’t right, start by looking at the people, the process, and the information. Meaning, when troubleshooting outcomes, investigate whether you are using the right resource, the best method, and whether you have enough complete and accurate information to make an informed decision.

With that in mind, here is a quick primer on logical fallacies.

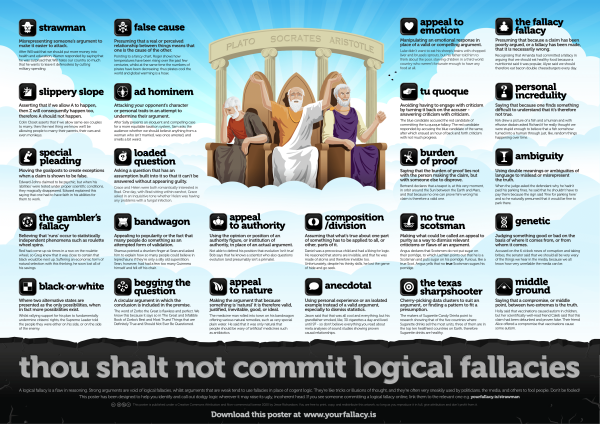

A logical fallacy is a flaw in reasoning. In other words, logical fallacies are like tricks or illusions of thought. As you might suspect, politicians and the media often rely on them. Recently, we discussed the Dunning-Kruger Effect … but that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Oxford Learning via InFact with Brian Dunning (Part 2, Part 3)

It is fun to identify which of these certain people (including yourself) use when arguing, deciding, or otherwise pontificating. To help, here is a short list of TWENTY LOGICAL FALLACIES:

They fall into three main types: Distraction (10), Ambiguity (5), and Form (5).

A. Fallacies of Distraction

1. Ad baculum (Veiled threat): "to the stick":

DEF.- threatening an opponent if they don’t agree with you; EX.- "If you don’t agree with me you’ll get hurt!"2. Ad hominem (Name-calling; Poisoning the well): "to the man":

DEF.- attacking a person’s habits, personality, morality or character; EX.- "His argument must be false because he swears and has bad breath."3. Ad ignorantium (Appeal to ignorance):

DEF.- arguing that if something hasn’t been proved false, then it must be true; EX.- "U.F.Os must exist, because no one can prove that they don’t."4. Ad populum: "To the people; To the masses":

DEF.- appealing to emotions and/or prejudices; EX.- "Everyone else thinks so, so it must be true."5. Bulverism: (C.S. Lewis’ imaginary character, Ezekiel Bulver)

DEF.- attacking a person’s identity/race/gender/religion; EX.- "You think that because you’re a (man/woman/Black/White/Catholic/Baptist, etc.)"6. Chronological Snobbery

DEF.- appealing to the age of something as proof of its truth or validity; EX.-"Voodoo magic must work because it’s such an old practice;" "Super-Glue must be a good product because it’s so new."7. Ipse dixit: "He said it himself":

DEF.- appealing to an illegitimate authority; EX.- "It must be true, because (so and so) said so."8. Red Herring (Changing the subject):

DEF.- diverting attention; changing the subject to avoid the point of the argument; EX.- "I can’t be guilty of cheating. Look how many people like me!"9. Straw Man:

DEF.- setting up a false image of the opponent's argument; exaggerating or simplifying the argument and refuting that weakened form of the argument; EX.- "Einstein's theory must be false! It makes everything relative–even truth!"10. Tu quoque: "You also"

DEF.- defending yourself by attacking the opponent; EX.- "Who are you to condemn me! You do it too!"

B. Fallacies of Ambiguity

1. Accent:

DEF.- confusing the argument by changing the emphasis in the sentence; EX.- "YOU shouldn’t steal" (but it’s okay if SOMEONE ELSE does); "You shouldn’t STEAL" (but it’s okay to LIE once in a while); "You SHOULDN’T steal (but sometimes you HAVE TO) ."2. Amphiboly: [Greek: "to throw both ways"]

DEF.- confusing an argument by the grammar of the sentence; EX.- "Croesus, you will destroy a great kingdom!" (your own!)3. Composition:

DEF.- assuming that what is true of the parts must be true of the whole; EX.- "Chlorine is a poison; sodium is a poison; so NaCl must be a poison too;" "Micro-evolution is true [change within species]; so macro-evolution must be true too [change between species]."4. Division:

DEF.- assuming that what is true of whole must be true of the parts; EX.- "The Lakers are a great team, so every player must be great too."5. Equivocation:

DEF.- confusing the argument by using words with more than one definition; EX.- "You are really hot on the computer, so you’d better go cool off."

C. Fallacies of Form

1. Apriorism (Hasty generalization):

DEF.- leaping from one experience to a general conclusion; EX.- "Willy was rude to me. Boys are so mean!"2. Complex question (Loaded question):

DEF.- framing the question so as to force a single answer; EX.- "Have you stopped beating your wife yet?"3. Either/or (False dilemma):

DEF.- limiting the possible answers to only two; oversimplification; EX.- "If you think that, you must be either stupid or half-asleep."4. Petitio principii (Begging the question; Circular reasoning):

DEF.- assuming what must be proven; EX.- "Rock music is better than classical music because classical music is not as good."5. Post hoc ergo propter hoc (False cause): "after this, therefore because of this;"

DEF.- assuming that a temporal sequence proves a causal relationship; EX.- "I saw a great movie before my test; that must be why I did so well."

For more on that, here is a fun and informative infographic by The School of Thought.

We must use logic as a spam filter: Fallacies are the junk mail of thought—fast, flashy, and costly when clicked.

Hope that helps.

via

via

Leave a Reply