Peak Capital is running an online roundtable in November with our CIO John DeTore, John Mauldin, and Sam Stovall. You can check with them to get the full answers from the various panelists, but I wanted to share some of John's answers ahead of time. I previously shared Part 1. This is Part 2 and will finish this piece.

November 2019 PCM Roundtable

Peak: Consensus suggests the U.S. economy is slowing and that trend will continue. What might cause an unexpected rise in GDP going into 2020?

John: Well, a cascading set of trade deals would now set us up for that. It would be politically beneficial for Trump to wrap them up soon. So that means 1) he will try really hard, and 2) other countries (and his political adversaries) will use that to their advantage. I have no idea who will win that one. For instance, look for the house to ignore USMCA until the election.

Peak: The Fed takes its cue from the economy, so it is unusual with virtually full employment and strong wage growth they are cutting rates, and everyone expects QE4. Any non-consensus views about the Fed's policy going forward?

John: Well, they are cutting rates not because the economy is weak, but because they figured out that they overdid it in 2018 by raising the rate. They started out too low, they raised it too much, and are now in the process of fixing it.

Peak: Earnings season started strong with better than expected earnings from banks. Are initial results going to be reflective of the broad market's earnings for the remainder of 2019?

John: Earnings are not going to be a problem for us.

Last year, earnings benefitted from very substantial corporate tax relief and deregulation. This will continue for several years, but the benefit is front-loaded, and the tailwind will ease off.

We fall into the trap of looking at year-over-year EPS growth to judge the strength of our public companies. They are earning good money! Profits are not being driven down by any undue systematic force. Even if they don’t grow fast, they are still quite profitable.

Peak: Looking out 12 months, 1 month prior to the 2020 election, do you believe the stock market will be higher, lower, or generally flat from today's level?

John: The market assumes Trump will win and very much will want Trump to win, if only to avoid the painful experiment with the far-left policies of the current Democratic candidates.

You would think Trump would be unbeatable given the success of the economy and a democratic candidate pool that is oddly positioned to the left of the Democratic party in general.

But there really is Trump Derangement Syndrome (TDS) in the country today …don’t remember there ever being a President with such venomous detractors since Nixon … right before his resignation. So, we can’t assume. And Hillary might get into the race which will cause the market to take off if only for the entertainment value.

The answer to the question is that I am biased to the market being higher. If it looks like Trump will probably lose the market will have a hard time with this and could be off quite a bit.

Peak: The search for yield has not gotten any easier in 2019. What concerns do you have for pension plans and retirees who require steady income?

John: A lot of concern. Long-term rates, in fact, act as a negotiation between generations. Retirees, who need income, lend their life assets to young families, who borrow for home formation. As discussed earlier, long-term rates are too low.

While “too-low” rates do in general stimulate the economy, lots of awkward or even negative side effects occur:

- Pensions go deeper into unfunded territory because of the assumed discounts on future obligations.

- Low rates mean low mortgage rates. While this is initially good for borrowers, there is an equilibrium that drives up housing prices. Most of America buys their home with a mortgage and set what they can afford based on what they can borrow. Low rates push housing prices up.

- While retirees get hurt by low rates, it's unclear if young families will get helped in the long run. They end up with more debt for the payment they can afford. It can lead to a housing price bubble.

- There are other disruptions of too-low rates like “zombie companies” supported by too-easy credit.

Not to sound all 50’s about it, the solution for income for retirees (that don’t pursue active management) might be to seek out strong US public companies that have significant dividend yields. The S&P yield is now competitive with bonds. Remember also that we have gone through a multi-decade process of accepting that stock-buybacks are often preferred by investors to dividend yields. You don’t just get the dividend payment, you get the buybacks in the form of capital appreciation.

Those who are interested in alpha should find approaches that will work in the new environment. The three major sources of return available to typical U.S. investors are bond yields, the stock market, and a return from active management.

As yields fall, active management must work less well to keep up. The bar has been lowered.

There has been a mass exodus from active management into index funds and ETFs. So many people I talk to say they don’t want to take the risk of active management. But a S&P index fund has more risk than most retirees should take with the core of their assets. Active management in general needs a careful new look by investors.

Peak: Switzerland, Germany and Japan have negative yields going well out on the yield curve. Do you expect negative yields at any point in the U.S.?

John: No … but I didn’t think they would go as low as they have so far either.

I’ve heard educated arguments that falling yields are a counter-intuitive result of too much government debt. But this just seems wrong-headed to me. I brought it up earlier: the yield of bonds is set by supply and demand. Supply is certainly up given our deficit spending, but, counter-intuitively, rates are down. I am left with only one good answer: demand is up more than supply.

My suspicion is that the culprit is the post-2008 waves of regulation with its haircuts to allowed leverage, and complex capital ratios that favor first-world sovereign bonds. I see no reason why so many would be willing to hold a bond at negative rates unless they really had no legal choice. The sky is not falling, there are many great places to invest capital for positive rates.

To answer the question, sooner or later we will better understand why negative rates happen. We should try and fix it. If we don’t, it's probably a matter of time 'til it happens here.

Peak: Correlations between stocks and bonds this year have made maintaining a diversified portfolio relatively easy. Anything on your radar that may make this more difficult in the future?

John: Bonds obviously respond to changes in interest rates. Stocks, through the P/E ratio, also respond to interest rates in the same way. Lower rates mean a higher P/E, all things being equal.

In periods of rapid rate changes or big changes in inflation expectations, the two asset classes will be correlated because they are both responding primarily to rate changes. Both will have positive returns when rates drop.

Hmm … but right now the market has refused to play this game. While the yields on bonds are in many cases at ALL TIME LOWS, the corresponding yields on stocks are near average. It is as if the stock market is saying: “these really low bond rates are crazy … this can't last for the next 5-10 years … I’m waiting this out.” If the market ends its obstinance and plays along, IT WOULD NEED A 50x P/E multiple. It might even be saying “The stock market is rational, but the bond market is a bubble.”

The stock market is responding to the EPS side of the equation, though. When EPS come though unexpectedly, the market rises. When perceived growth increases the market rises (and the bond market falls).

In addition, the market has been really (too) preoccupied with politics and the political divide in the country right now.

This adds up to a low correlation between the stock and bond markets. It is lower than usual and will eventually go back to normal.

Catalysts that would cause low correlation to rise:

- it will happen naturally if bond yields and P/E ratios normalize,

- it will also happen if we go into a recession and the stock market re-adopts it “bad news is good news” posture and rises with every rate lowering move by the Fed.

Peak: If I gave you a magic wand that allowed you to change just one thing about the financial markets or investing, what would it be?

John: (I genuinely, seriously wish I had invented high-frequency trading back when it was fun and innovative. I promise I would put my $B’s to good use.)

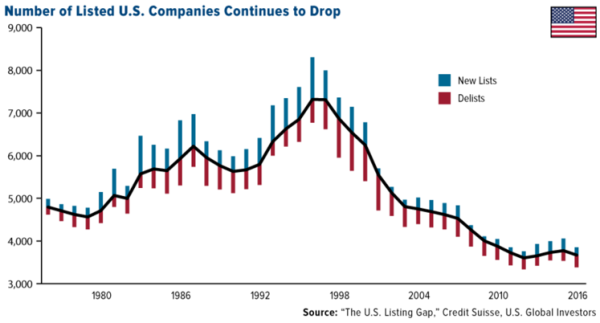

But seriously, I wish we would pass legislation (tax or regulation) that made it attractive to spinoff companies rather than merge them. Many evils in our economy stem from too few firms that are too large and influential (drugs, tech, banking). This is doable and would affect income disparity more than any of the proposals I hear from politicians. It would add many more senior and middle managers who are talented and can drive innovation better with some independence.

via USFunds

via

via