When most of us think about debt, we picture credit cards, student loans, or a car payment. It’s concrete, immediate, and tied to something we’re personally responsible for repaying.

Global debt is the opposite. It’s so large and abstract that it almost feels made up — like a number you’d hear in a sci-fi movie — not a real economic measure that affects everyday life.

Why Global Debt Is Harder to Understand

Your personal balance sheet is simple: money in, money out.

The global one mixes governments, central banks, currencies, alliances, and geopolitics. It’s not intuitive, which is why people either ignore the topic or assume the worst.

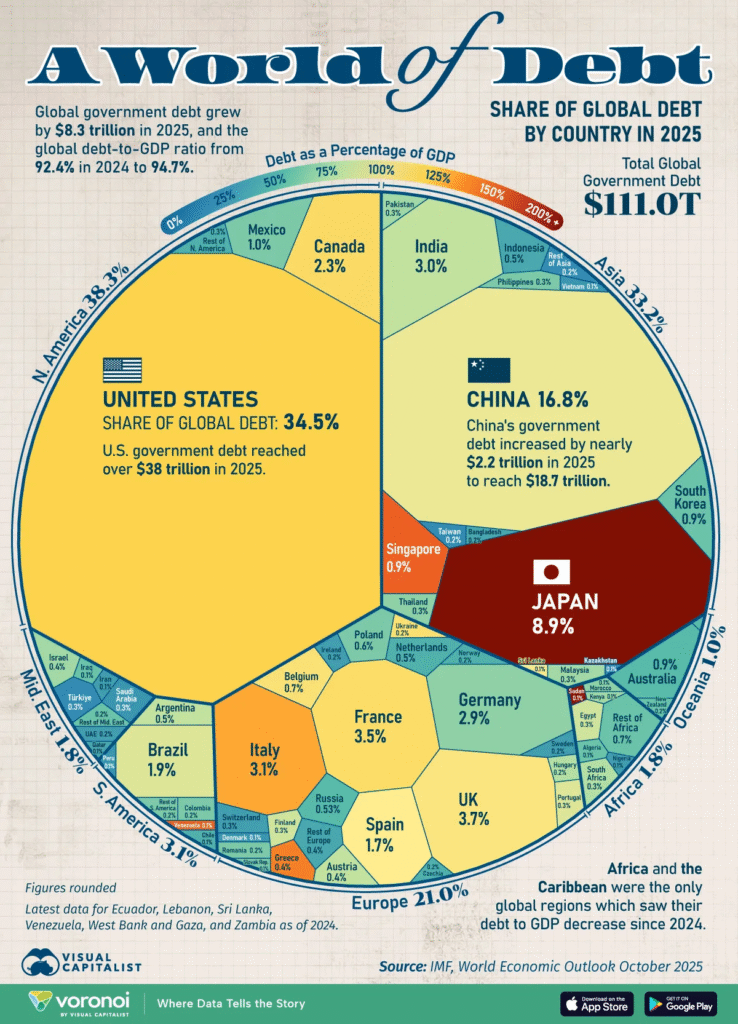

via visualcapitalist

The U.S. accounts for just over 34% of that number, or approximately 125% of our current GDP. Meanwhile, I remember writing about the Republican National Convention, which marked the moment our national debt crossed the $16 trillion threshold in 2012.

Today, we’re far beyond that. If you split today’s national debt evenly, every American would “owe” over $100,000.

If the ten wealthiest people donated their entire fortunes, we would only cover about 5% of the national debt.

Should We Be Worried?

Some argue that our debt is too high and threatens economic stability, the dollar’s strength, and the job market.

In reality, there are only five ways to reduce national debt:

- Increase taxes

- Decrease spending

- Restructure the debt

- Monetize the debt

- Default

None of those options is fun. Most seem politically impossible.

Understanding The Current System

The idea behind our current global debt structure is that if two nations are mutually obligated and dependent on each other, they are less likely to go to war. And that has held relatively true. Of course, it’s not a perfect system (and it could break down), but it’s working better than previous systems (such as the balance of power).

In some ways, it’s fake money (essentially digital ledger entries), so our debts don’t seem insurmountable or fatal. Our economy is so reliable that we’re allowed to continue borrowing. Debt is an integral part of the economic machine – it can be argued that we wouldn’t have money – or markets – without debt.

Ray Dalio made a straightforward (but not oversimplified) 30-minute animated video that answers the question,” How does the economy really work?” Click to watch.

via Ray Dalio

The global economy has grown enormously over the last 50 years as developing nations have prospered. The average global GDP per capita has gone from ~$1000 to over $10,000 in my lifetime.

As economies grow, populations rise, and transactions multiply, the amount of money circulating in the system has to grow too.

More Activity → More Money → More Debt.

It’s not automatically a crisis. It’s often a sign of growth. With that said, $111 trillion is still an almost unfathomable number.

A Lesson In Scale

Even though you may not need to worry about our global debt number right away, I still think it’s worth putting it in context. What follows are several examples to help you fathom the unfathomable.

Humans are notoriously bad at large numbers. In part because it’s hard to wrap our minds around something of that scale. We’re wired to think locally and linearly, not exponentially.

Humans struggle to grasp large number magnitudes because our brains evolved to handle small, practical numbers essential for daily survival, such as counting food items or group members, rather than abstract, massive quantities. The human brain processes small numbers with an innate “number sense,” which becomes much less precise as numbers get larger, relying on a mental number line that tends to compress and approximate rather than distinctly represent high values.

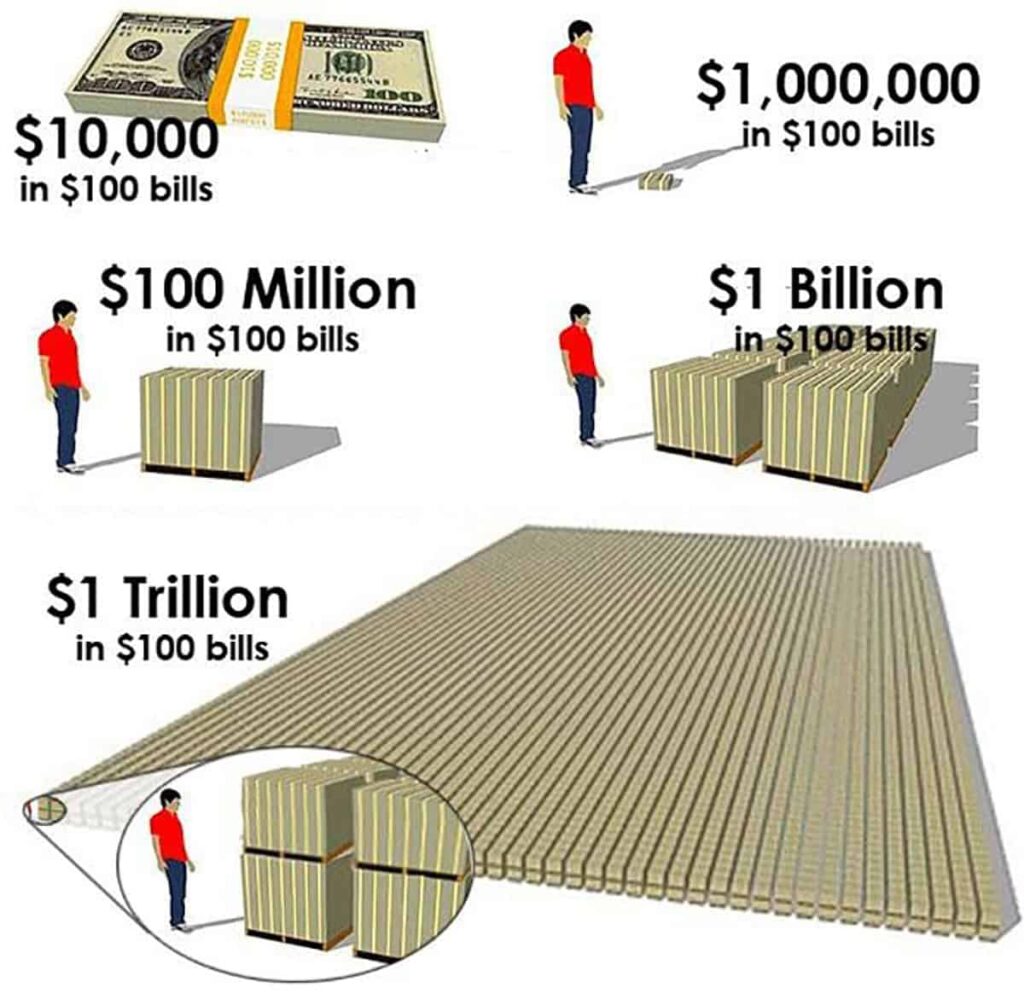

Here are a couple of ways to help you understand a trillion dollars. First, let’s look at it in terms of physical money and the space it takes to store it.

We’ll start with a $100 bill, currently the largest U.S. denomination in general circulation, and pretty handy to have and hold.

The image below follows the progression. A packet of one hundred $100 bills (totaling $10,000) is less than half an inch thick — and small enough to fit in your pocket. The next pile shown is $1 million (100 packets of $10,000). You could stuff that into a duffel bag and walk around with it. By the time you get to $100 million, it starts to look more impressive … but it still fits neatly on a standard pallet. Skipping forward to $1 trillion, well, it’s a million million. It’s a thousand billion. It’s a one followed by 12 zeros. In the final image below, notice that those pallets are double-stacked and would fill a stadium.

Visualizing How Big Is a Trillion.

Next, let’s look at spending over time. Here’s a simple example. If you were to spend a dollar every second for an entire day, you would pay $86,400 each day. With a million dollars, you could spend $1 every second for about twelve days. With a billion dollars, you can do that for over 31 years. With a trillion dollars, you can do that for 31,000+ years.

That means it would take over 300 thousand years to spend the global public debt at that rate.

I’m sure many of you make over six figures a year. But, it would still take you 10 million years – if you spent none of it – to make $1 trillion. What about $100 trillion? Again, unfathomable.

Let’s try explaining it, using time, in a different way. One hundred thousand seconds is just over a day. A million seconds was 11 days ago. A billion seconds ago from today? That was in 1994. One trillion seconds is … slightly over 31,688 years. That would have been around 29,688 B.C., which is roughly 24,000 years before the earliest civilizations began to take shape. Pretty crazy.

Should We Be Panicking?

Not necessarily. But we should understand it.

The number is enormous, but it exists within a system built to handle them. The real risk isn’t the size, it’s how governments respond, how economies evolve, and whether confidence in the system holds.

And confidence, ironically, is the most valuable currency.

Do you think the world is still confident in the future? And what about America? More or less than 4 or 8 years ago?

Despite the pessimism, I’m still optimistic.

Let me know how you feel.

Leave a Reply