Remote work has been increasingly popular because of the pandemic … but even as more people have vaccines, and some are even getting booster shots, the love for remote work stays.

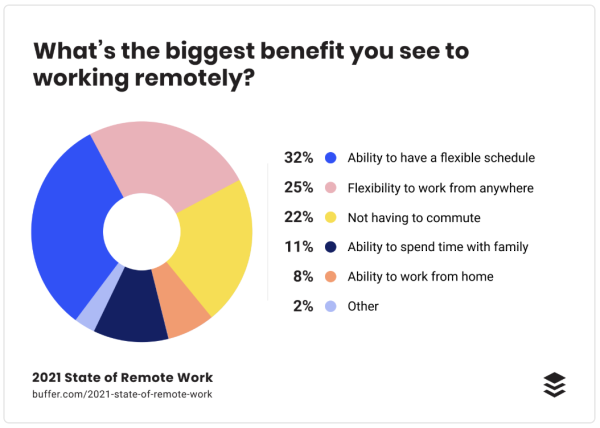

via Buffer – State of Remote Work 2021

via Buffer – State of Remote Work 2021

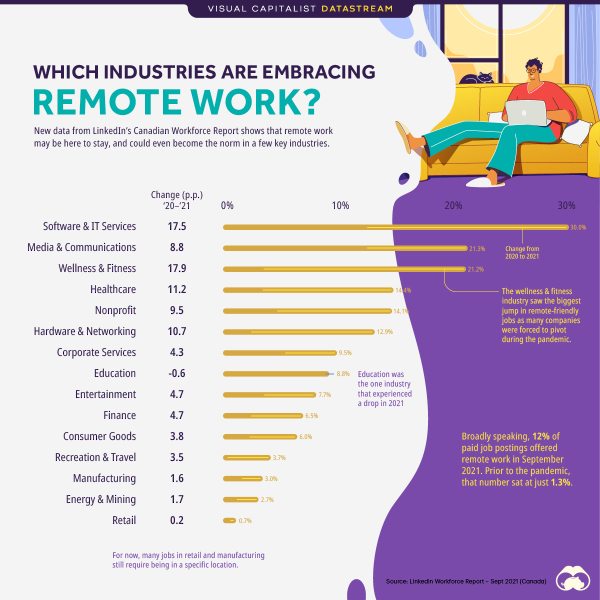

But some industries are adopting it more than others.

I'll be honest … when I first saw this, I was like, "Retail's that low? That can't be right". But then I realized… I never really go to stores. What would I know?

Seeing the rise of remote work in Media & Tech is unsurprising. But, I will be curious to see what percentage of these businesses stay remote as we move further away from the "worst" of Covid-19.

As I mentioned in this video, hybrid solutions are the answer. There's too much benefit to the culture of companies that spend real time together in person. While I believe productivity can remain high at home or in the office, the sense of camaraderie is hard to sustain if you rarely see each other in real life.

That being said, employees are reporting being happier and more productive at home. Consequently, I wouldn't bet on the move back to the office happening quickly. Meanwhile, companies also are suffering through the "great resignation." Clearly, the game has changed – and so must their strategies and tactics.

The culture of work is in a massive period of transformation. Regardless of where your specific company or industry ends up, all businesses will have to increase the amount of employee care they provide. Just as the heart of AI is still human, so is the heart of our businesses.

You shouldn't be forced to take care of your employees … you should want to. This past year+ has been challenging for everyone, and it's important to keep that in mind as you make decisions.

via

via

via

via  via

via