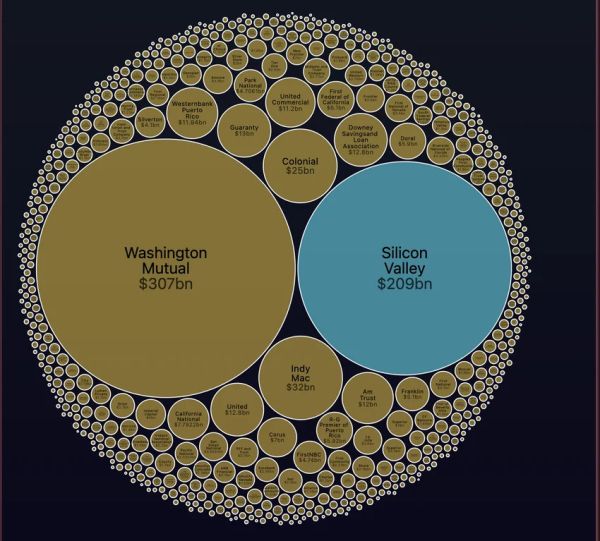

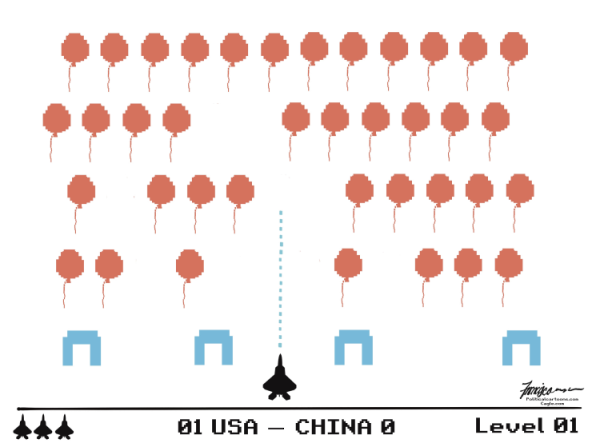

This week, the rapid collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (“SVB”) stunned the venture capital and startup community. SVB customers initiated withdrawals of $42bn in a single day (a quarter of the bank’s total deposits), and it could not meet the requests. By Friday, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (the “FDIC”), the US bank regulator that guarantees deposits of up to $250,000) declared SVB insolvent and took control. The run was so swift SVB’s coffers were drained in full, and the bank carried a “negative cash balance” of nearly $1bn.

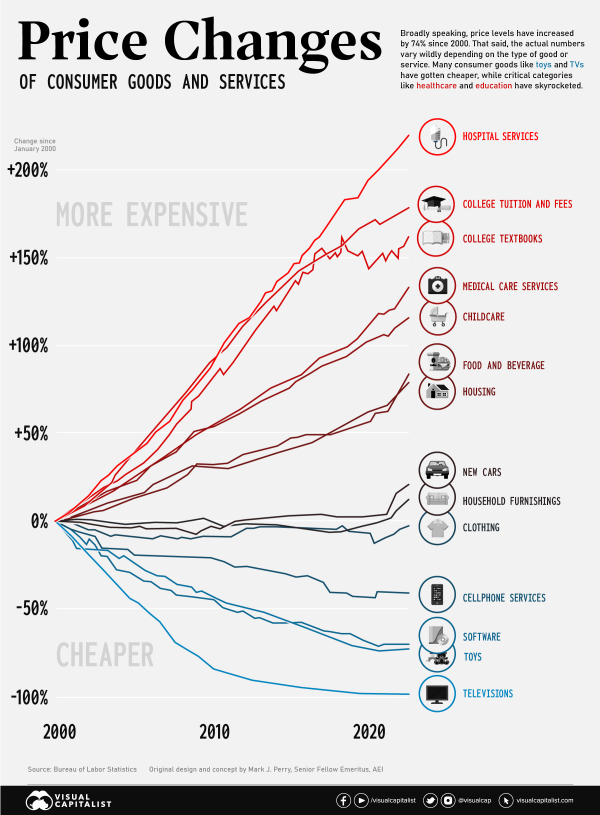

Silicon Valley Bank’s death spiral started on Wednesday when it told investors that it needed to raise over $2 billion … in large part due to unforced errors. To start, its balance sheet took a massive hit because of inflation and the subsequent rise in interest rates. Deposits in the bank grew massively from 2019 to 2021, and interest rates were low, so the bank heavily invested in treasury bonds. Those bonds were yielding an average of only 1.79% at the time. When the Fed jacked up rates, the approximately $80 billion SVB had in bonds cratered in value. Suddenly, SVB customers began a hysteric bank run, ultimately withdrawing $42 billion worth of deposits by the end of Thursday. By Friday, the FDIC had seized the bank in the most significant failure since the Great Recession. To make matters worse, 97% of deposits in the bank were above the FDIC insurance threshold and thus uninsured.

When I started writing this article, it was unclear what would happen to the thousands of VCs, PE Funds, and startups heavily reliant on SVB. Over 65,000 startups were worried about missing payroll, and it was all dependent on the whim of the FDIC. Luckily for them, they took aggressive action and agreed to backstop all depositors – hoping to prevent runs on any other financial institutions.

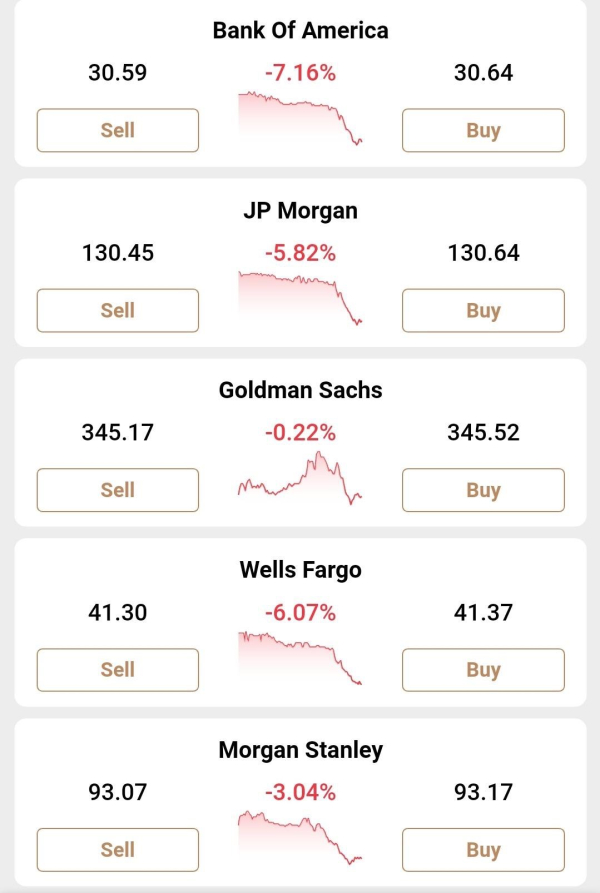

Meanwhile, the Dow posted its worst week since June on the back of the big banks being hit with big losses.

The FDIC stepping in is part of a broader effort by regulators to reassure customers that their money is safe. For example, the US central bank added it was “prepared to address any liquidity pressures that may arise.”

The Fed’s new facility, the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), will offer loans of up to one year to lenders who pledge as collateral US Treasuries, agency debt, mortgage-backed securities, and other “qualifying assets.”

Those assets will be valued at par, and the BTFP will eliminate an institution’s need to quickly sell those securities in times of stress. The Fed said the facility would be big enough to cover all US uninsured deposits. The discount window, where banks can access funding at a slight penalty, remains “open and available,” the central bank added.

Officials on Sunday said that the taxpayer would bear no losses stemming from the resolution of deposits. A levy on the rest of the banking system would fund any shortfall. They added shareholders and certain unsecured debtholders would not be protected.

A Look at How This Happened

We’ve already touched on the bank run and what caused it … but let’s dive deeper.

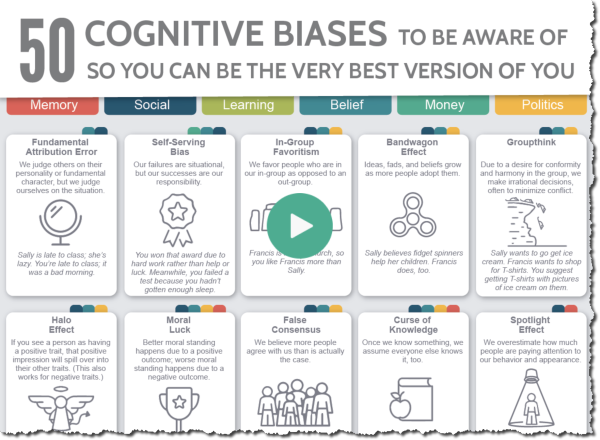

One of the biggest risks to SVB’s business model was catering to a very tightly-knit group of investors who exhibit herd-like mentalities. The problem with a business model like that is that when capital dries up, the deposits flee. Unfortunately, that sounds like a bank run waiting to happen … and it did.

The situation created a prisoner’s dilemma for depositors: I’m fine if they don’t draw their money, and they’re fine if I don’t draw mine. But once some started withdrawing, others followed suit.

Part of what started the run was SVBs decision to search for yield in an era of ultra-low interest rates. SVB ramped-up investment in a portfolio of highly rated government-backed securities, A significant portion of those in fixed-rate mortgage bonds carrying an average interest rate of just 1.64 percent. While slightly higher than the meager returns it could earn from short-term government debt, the investments locked the cash away for more than a decade and exposed it to losses if interest rates rose quickly.

When rates rose sharply last year, the portfolio’s value fell by $15bn, almost equal to SVB’s total capital. If SVB were forced to sell any of the bonds, it would risk becoming technically insolvent.

Although SVB’s deposits had been dropping for four straight quarters as tech valuations crashed from their pandemic-era highs, they plunged faster than expected in February and March. As a result, SVB decided to liquidate almost all of the bank’s “available for sale” securities portfolio and reinvest the proceeds in shorter-term assets to earn higher interest rates and improve the pressure on its profitability.

The sale meant taking a $1.8bn hit, as the value of the securities had fallen since SVB had purchased them due to surging interest rates.

To compensate for this, SVB arranged for a public offering of the bank’s shares, led by Goldman Sachs. It included a large investment from General Atlantic, which committed to buying $500mn of the stock. Although that deal was announced on Wednesday night, by Thursday morning, the deal was failing. SVB’s decision to sell the securities had surprised some investors and signaled to them that it had exhausted other avenues to raise cash. Some “smart” VC clients directed their portfolio clients to withdraw their deposits en masse to avoid losing it all.

What happened was the “perfect storm.” Many say it was predictable, especially after a decrease in regulation (which the bank’s management successfully lobbied for in 2015).

For now, SVB seems like an outlier, with its unusual (and specific) clientele. Still, there’s already nervousness for other small/regional banks … and there’s bubbling fear about the system as a whole.

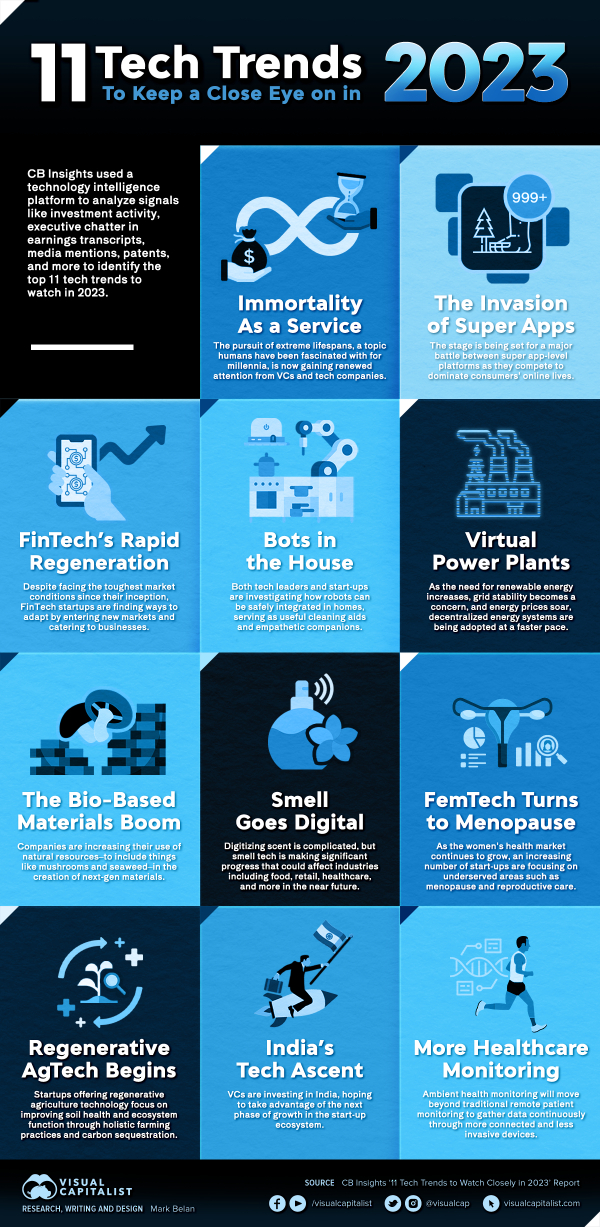

Where Do We Go From Here?

My first question is, should the FDIC raise the insurance limit above 250K? While Giannis Antetokounmpo might have his money in 50 banks to keep it insured, it doesn’t seem a reasonable expectation of small companies that need liquidity for payroll and other monthly expenses. While some might be happy to see a bank potentially penalized for perceived recklessness, you also have to consider the clientele of this bank – many of the innovators that are driving the future of technology (or at least, hoping to).

My second question is, where were the regulators? The issues that led to this disaster were pointed out publicly months before this happened. Are more regulations required to ensure trust in the American financial system? Or is this a free market where pain and pleasure point out the evolutionary path?

What happens when another bank fails the same way? Do we continue to find a way to bail them out?

Trust in the Fed – and the government as a whole – is low. It’s one of the reasons why people are so interested in cryptocurrency and the blockchain. As a result, we’re at a bit of a crossroads. Various governmental agencies want to assure you your money is safe, but there’s no belief that will always be the case.

SVB failed, in part, due to their own mistakes … but they also failed due to herd mentality and negative sentiment. Had people felt confident in this 40+ year-old bank, business might have continued as usual.

And, what does this mean for banks and regulation as a whole? Perception is often more important than reality in the case of markets, pricing, and a host of other supposedly logic-and data-based decisions. Clearly, Markets are not rational … that’s why you shouldn’t try to predict them. Even scarier is the potential lack of trust in banks’ ability to meet the needs of their stakeholders. There are countless banks with more than 50% of their money in uninsured deposits … will companies want to bank with them if there aren’t safeguards protecting them?

A big crisis was averted this time … but this won’t be the last crisis for banks.

As news continues to shake out, I’ll give more of my thoughts, but for now, I want to watch more and see what changes.

For a bonus laugh, here’s Jim Cramer calling Silicon Valley Bank a buy a month ago.

via CNBC Television

via

via