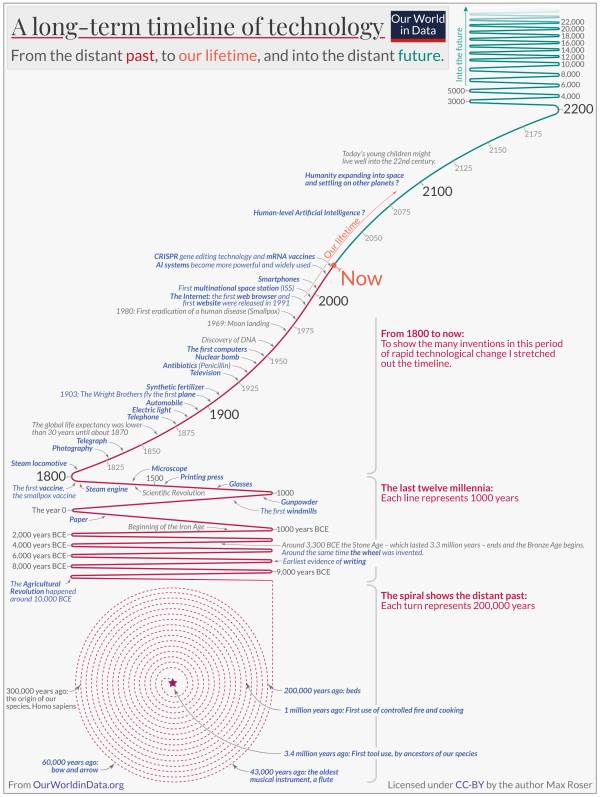

Every year, Stanford puts out an AI Index1 with a massive amount of data attempting to sum up the current state of AI.

Last year it was 190 pages … now it's 386 pages. The report details where research is going and covers current specs, ethics, policy, and more.

It is super nerdy … yet, it's probably worth a skim. Here are some of the highlights that I shared last year.

Here are a few things that caught my eye and might help set some high-level context for you.

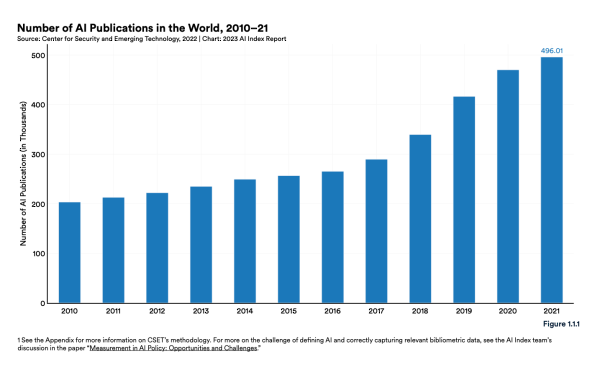

Growth Of AI

via 2023 AI Index Report

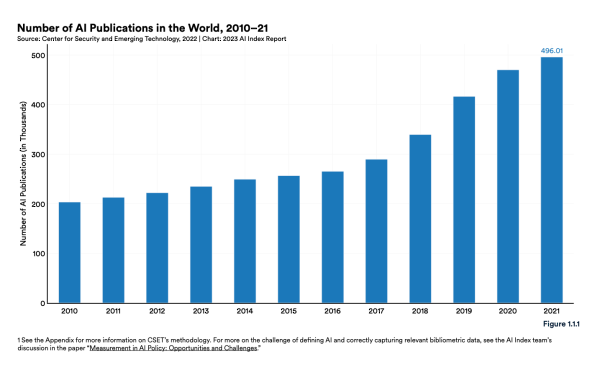

One thing that's very obvious to the world right now is that the AI space is growing rapidly. And it's happening in many different ways.

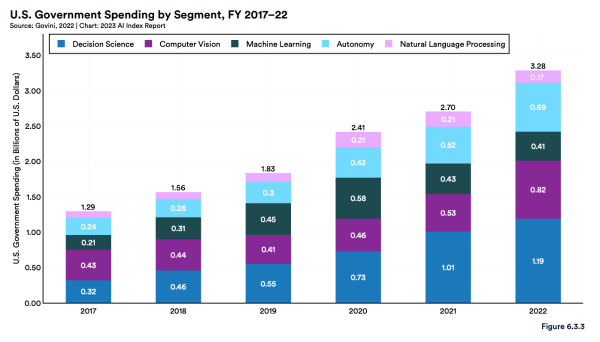

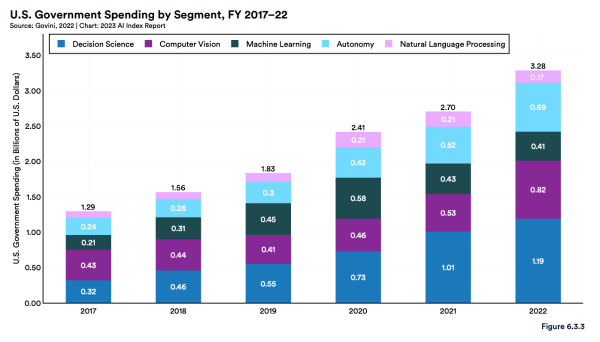

Over the last decade, private investment in AI has increased astronomically … Now, we're seeing government investment increasing, and the frequency and complexity of discussion around AI is exploding as well.

A big part of this is due to the massive improvement in the quality of generative AI.

Technical Improvements in AI

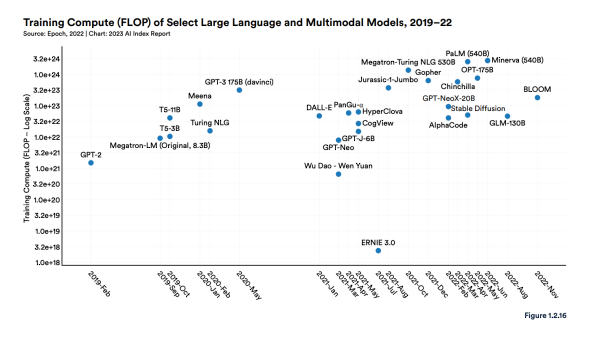

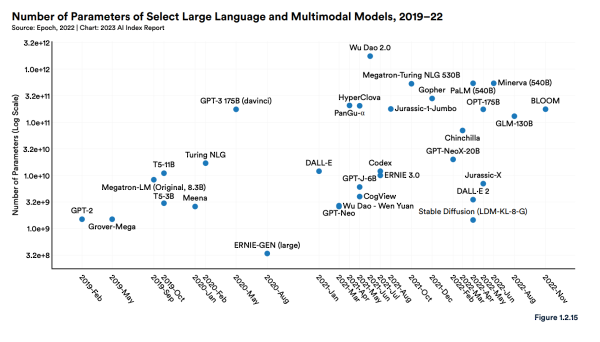

via 2023 AI Index Report

via 2023 AI Index Report

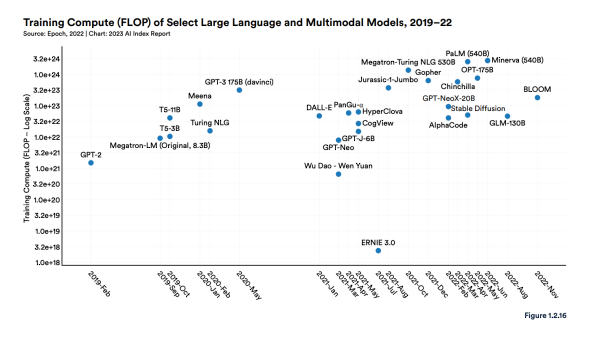

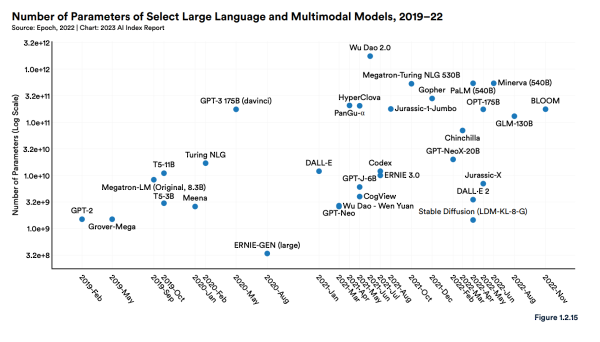

This isn't the first time I've shared charts of this nature, but it's impressive to see the depth and breadth of new AI models.

For example, Minerva, a large language and multimodal model released by Google in June of 2022, used roughly 9x more training compute than GPT-3. And we can't even see the improvements already happening in 2023 like with GPT-4.

While it's important to look at the pure technical improvements, it's also worth realizing the increased creativity and applications of AI. For example, Auto-GPT takes GPT-4 and makes it almost autonomous. It can perform tasks with very little human intervention, it can self-prompt, and it has internet access & long-term and short-term memory management.

Here is an important distinction to make … We're not only getting better at creating models, but we're getting better at using them, and they are getting better at improving themselves.

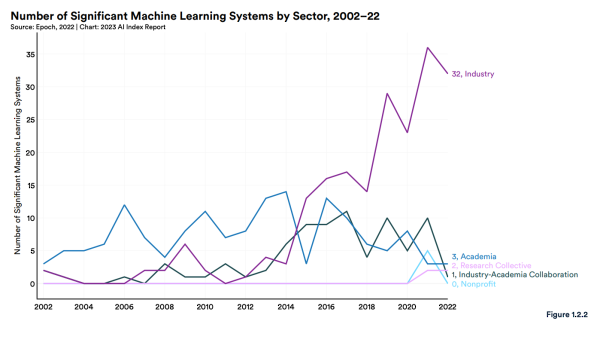

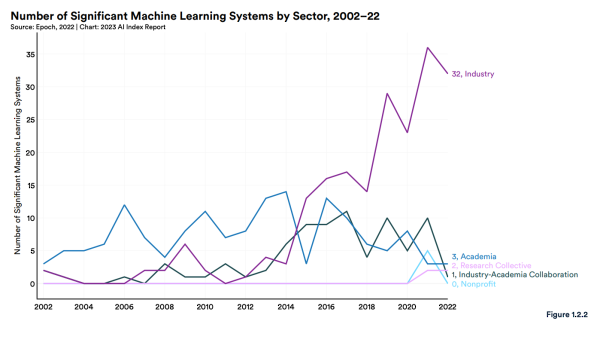

All of that leads to one of the biggest shifts we're currently seeing in AI – which is the shift from academia to industry. This is the difference between thinking and doing, or promise and productive output.

Jobs In AI

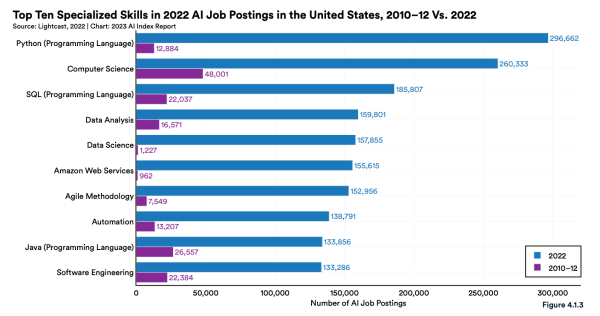

via 2023 AI Index Report

via 2023 AI Index Report

In 2022, there were 32 significant industry-produced machine learning models … compared to just 3 by academia. It's no surprise that private industry has more resources than nonprofits and academia, And now we're starting to see the benefits from that increased surge in cashflow moving into artificial intelligence, automation, and innovation.

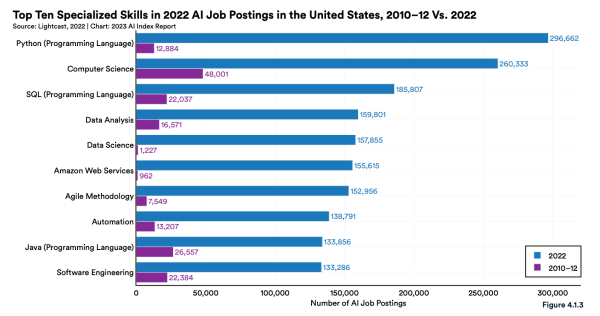

Not only does this result in better models, but also in more jobs. The demand for AI-related skills is skyrocketing in almost every sector. On top of the demand for skills, the amount of job postings has increased significantly as well.

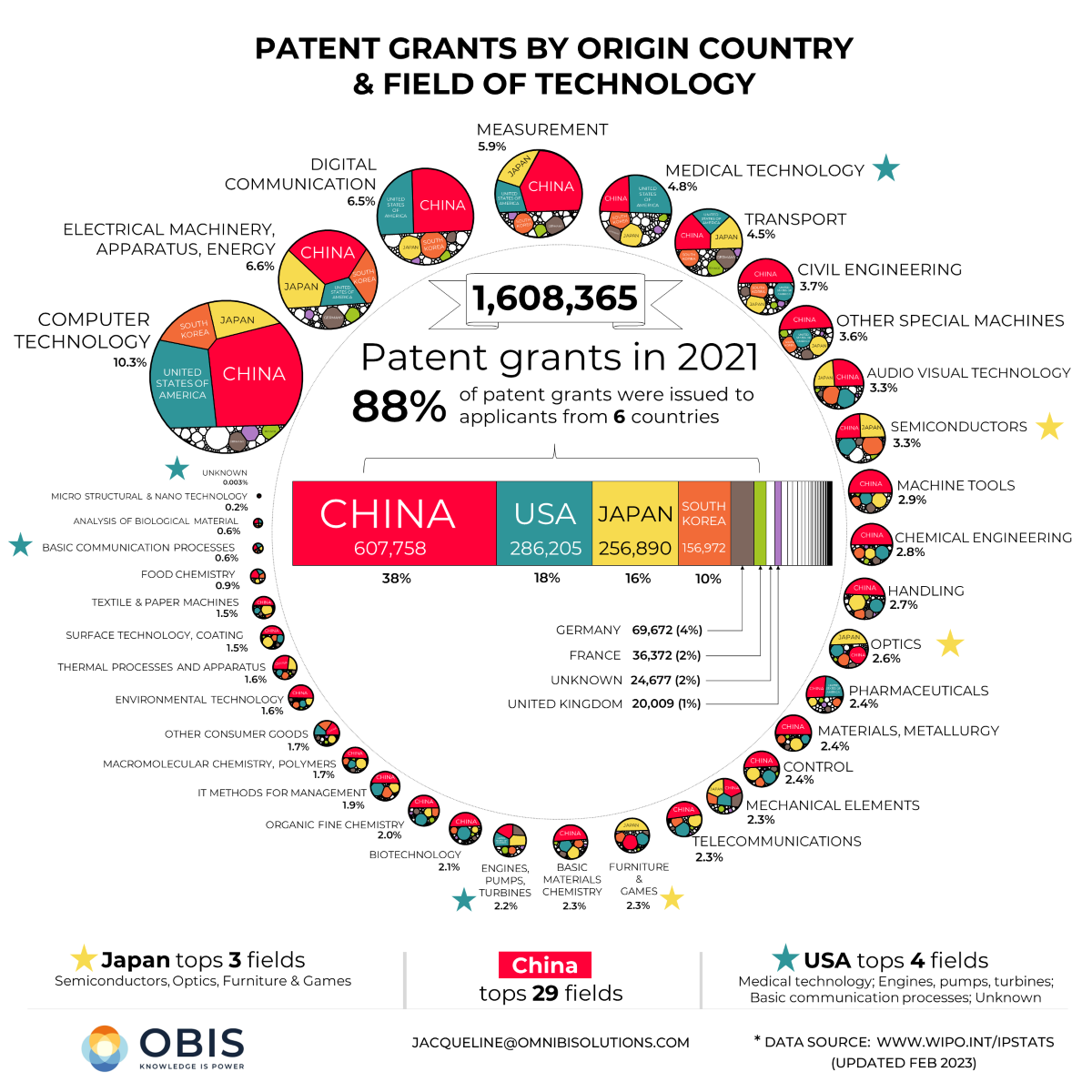

Currently, the U.S. is leading the charge, but there's lots of competition.

The worry is, not everyone is looking for AI-related skills to improve the world. The ethics of AI is the elephant in the room for many.

AI Ethics

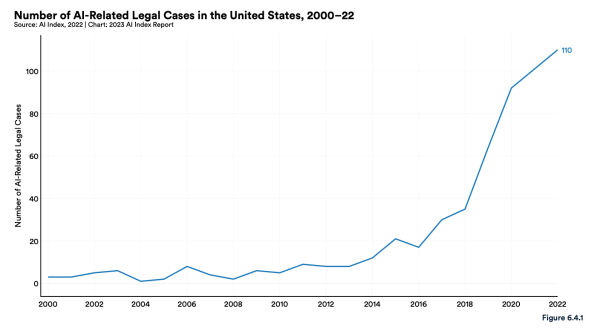

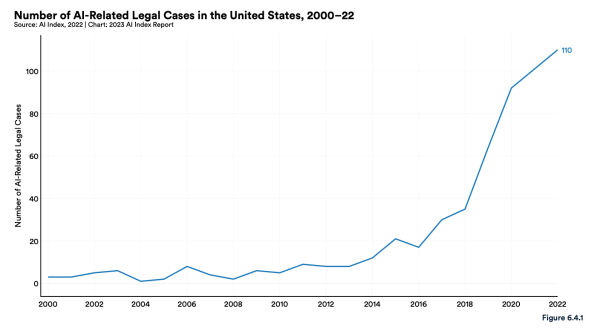

via 2023 AI Index Report

The number of AI misuse incidents is skyrocketing. Since 2012, the number has increased 26 times. And it's more than just deepfakes, AI can be used for many nefarious purposes that aren't as visible.

Unfortunately, when you invent the car, you also invent the potential for car crashes … when you 'invent' nuclear energy, you create the potential for nuclear bombs.

There are other potential negatives as well. For example, many AI systems (like cryptocurrencies) use vast amounts of energy and produce carbon. So, the ecological impact has to be taken into account as well.

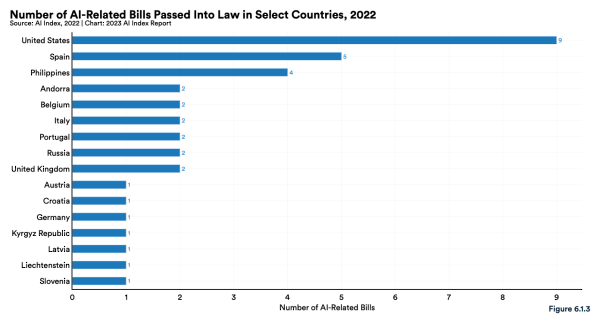

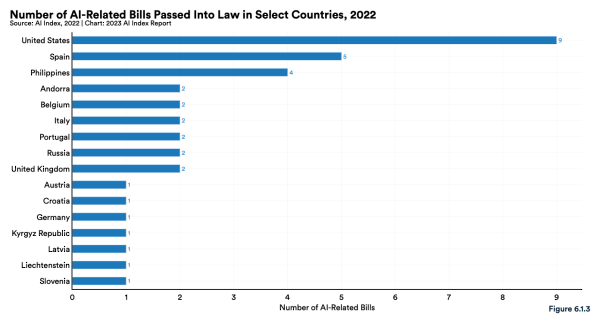

Luckily, many of the best minds of today are focused on how to create bumpers to rein in AI and prevent and discourage bad actors. In 2016, only 1 law was passed focused on Artificial Intelligence … 37 were passed last year. This is a focus not just in America, but around the globe.

Conclusion

Artificial Intelligence is inevitable. It's here, it's growing, and it's amazing.

Despite America leading the charge in A.I., we're also among the lowest in positivity about the benefits and drawbacks of these products and services. China, Saudi Arabia, and India rank the highest.

If we don't continue to lead the charge, other countries will …Which means we need to address the fears and culture around A.I. in America. The benefits outweigh the costs – but we have to account for the costs and attempt to minimize potential risks as well.

Pioneers often get arrows in their backs and blood on their shoes. But they are also the first to reach the new world.

Luckily, I think momentum is moving in the right direction. Watching my friends start to use AI-powered apps, has been rewarding as someone who has been in the space since the early '90s.

We are on the right path.

Onwards!

_____________________________________

1Nestor Maslej, Loredana Fattorini, Erik Brynjolfsson, John Etchemendy, Katrina Ligett, Terah Lyons, James Manyika, Helen Ngo, Juan Carlos Niebles, Vanessa Parli, Yoav Shoham, Russell Wald, Jack Clark, and Raymond Perrault, “The AI Index 2023 Annual Report,” AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, April 2023. The AI Index 2023 Annual Report by Stanford University is licensed under

via

via

via

via