Today was Super Bowl Sunday 2025. As a fan, I found myself rooting for the Philadelphia Eagles today. But at times, I was rooting for Patrick Mahomes and the Chiefs out of respect for the talent and the incredible record they’ve compiled.

Meanwhile, it also made me think about my home team, the Dallas Cowboys, and how long it’s been since we’ve had any real post-season success.

Obviously, the Jones family has done many things right. According to Forbes, for the ninth straight year, the Dallas Cowboys are the world’s most valuable sports team, worth an estimated $10.1 billion — the first to cross the 11-figure threshold and $1.3 billion beyond their closest competition.

They’ve mastered winning in the business sense, even when they struggle on the field.

Jerry Jones does a lot right in building his “Disney Ride.” However, this post will focus more on what the coaches and players do to win.

Business Lessons From the NFL

I’m regularly surprised by the levels of innovation and strategic thinking I see in football.

Football is something I used to love to play. And it is still something that informs my thoughts and actions.

Some lessons relate to teamwork, while others relate to coaching or management.

Some of these lessons stem back to youth football … but I still learn from watching games – and even more, from watching Dallas Cowboys practices at The Star.

Think about it … even in middle school, the coaches have a game plan. There are team practices and individual drills. They have a depth chart listing the first, second, and third choices to fill specific roles. In short, they focus on the fundamentals in ways that most businesses don’t.

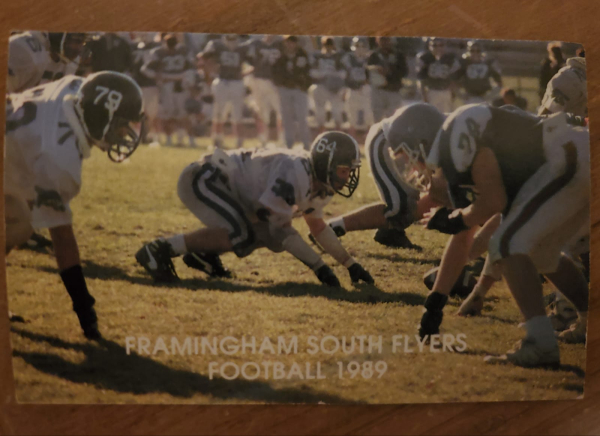

The picture below is of my brother’s high school team way back in 1989. While lots have changed since then, much of what we will discuss in this post remains timeless.

Losing to an 8th Grade Team

The scary truth is that most businesses are less prepared for their challenges than an 8th-grade football team. That might sound disrespectful – but if you think about it … it’s pretty accurate. Here is a short video highlighting what many businesses could learn from observing how organized sports teams operate, particularly in setting goals and effectively preparing for challenges.

via YouTube.

If you are skimming, here is a quick summary of the key points in the video.

Organization and Preparation

- Structure: Football teams have a clear hierarchy, including a head coach, assistant coaches, and trainers.

- Practice: Teams engage in regular practice sessions to prepare for games, emphasizing the importance of training.

- Game Plan: They develop strategies and a game plan before facing opponents, including watching game films to understand their competition.

Dynamic Strategy

- Adaptability: Teams adjust their strategies based on the game’s flow, recognizing whether they are on offense or defense.

- Audibles: Just as a football team may call an audible when faced with unexpected defensive setups, businesses should adapt their strategies in real time.

Learning From Experience

- Post-Game Analysis: Coaches review game films to identify what worked and what didn’t, learning from past experiences to improve future performance.

- Continuous Improvement: Ongoing training is crucial in businesses, similar to how football players receive coaching during practice to enhance their skills.

Importance of Coaching

- Role of Coaches: Coaching is crucial for developing talent and focusing on achieving defined goals.

- Encouragement of Growth: Active coaching leads to better outcomes and overall improvement.

A Deeper Look Into the Lessons

There is immense value in the structured coaching and preparation that sports teams exemplify. Here are some thoughts to help businesses adopt similar principles that foster teamwork, adaptability, and continuous improvement.

Vince Lombardi once famously started training camp by announcing, “Gentlemen, this is a football.” He stressed the hidden power of mastering the fundamentals. Beyond that, he believed that how you do something is how you tend to do everything … which led to his famous quote, “Football is not just a game, but a way of life.”

So, let’s start at the beginning.

Football teams think about how to improve each player, how to beat this week’s opponent, and then how to string together wins to achieve a higher goal.

The team thinks of itself as a team. They expect to practice. And they get coached.

In addition, there is a playbook for both offense and defense. And they watch game films to review what went right … and what they can learn and use later.

Contrast that with many businesses. Entrepreneurs often get myopic … they get focused on today, focused on survival, and they lose sight of the bigger picture and how all the pieces fit together.

The amount of thought and preparation that goes into football – which is ultimately a game – is a valuable lesson for business.

What about when you get to the highest level? If an 8th-grade football team is equivalent to a typical business, what about the businesses that are killing it? That would be similar to an NFL team.

Let’s look at the Cowboys.

Practice Makes Perfect

How you do one thing is how you do everything. So, they try to do everything right.

Each time I’ve watched a practice session, I’ve come away impressed by the amount of preparation, effort, and skill displayed.

During practice, there’s a scheduled agenda. The practice is broken into chunks, each with a designed purpose and a desired intensity. There’s a rhythm, even to the breaks.

Every minute is scripted. There’s a long-term plan to handle the season … but, there was also a focus on the short-term details and their current opponent.

They alternate between individual and group drills. Moreover, the drills run fast … but for shorter periods than you’d guess. It is bang-bang-bang – never longer than a player’s attention span. They move from drill to drill, working not just on plays but also on skill sets (where are you looking, which foot you plant, how to best use your hands, etc.).

They use advanced technology to get an edge (including player geolocation monitoring, biometric tracking, medical recovery devices, robotic tackling dummies, and virtual reality headsets).

They don’t just film games; they film the practices … and each player’s individual drills. Coaches and players get a personalized cut on their tablets when they leave. It is a process of constant feedback and constant improvement. Everything has the potential to be a lesson.

Beyond The Snap

The focus is not just on the players and the team. They focus on the competition as well. Before a game, the coaches prepare a game plan and have the team watch videos of their opponent to understand tendencies and mentally prepare for what will happen.

During the game, changes in personnel groups and schemes keep competitors on their toes and allow the team to identify coverages and predict plays. If the offense realizes a play has been expected, they call an audible based on what they see in front of them. Coaches from different hierarchies work in tandem to respond faster to new problems.

After the game, the film is reviewed in detail. Each person gets a grade on each play, and the coaches make notes for each person about what they did well and what they could do better.

Think about it … everyone knows what game they are playing … and for the most part, everybody understands the rules and how to keep score (and even where they are in the standings). Even the coaches get feedback based on performance and look to others for guidance.

Imagine how easy that would be to do in business. Imagine how much better things could be if you did those things.

Challenge accepted.

And, just for fun, here’s a video of me doing a cartwheel after a Dallas Cowboys win.

Sports make you do funny things.

Whether you are watching or playing – Enjoy the game!

Leave a Reply