Last week, we took a look at oil reserves amid Venezuela-related headlines. However, knowing where oil reserves are isn’t enough to understand the entire picture.

When the U.S. recently eased sanctions on Venezuela, headlines touted the country’s 300 billion barrels of proven reserves — the world’s largest. But here’s the paradox: Venezuela produces less than 1% of the global oil supply. What explains the gap between paper wealth and market irrelevance?

The short answer is, in 2026’s energy landscape, not all barrels are created equal.

Why Reserves Data Misleads

To understand why those headlines can mislead, it helps to look at how the market actually prices different types of crude.

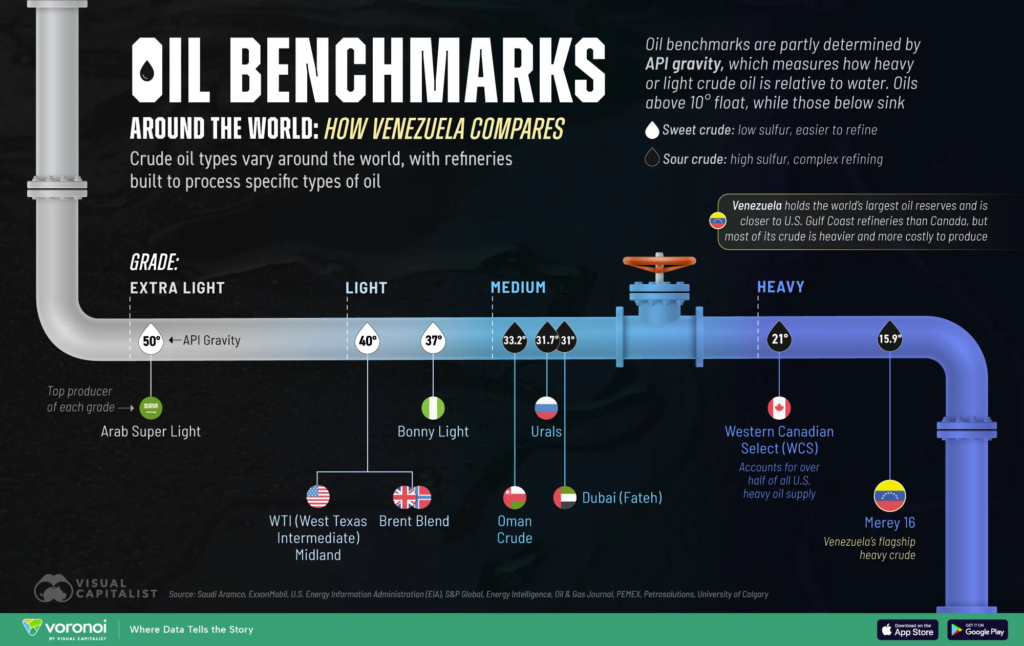

For investors, reserves are table stakes; the edge lies in understanding which barrels can become durable cash flows. To see why, it helps to start with how the market actually prices crude. For example, oil benchmarks are determined by API gravity (which measures crude density relative to water) and sulfur content.

While Venezuela holds the world’s largest reserves, most of its crude is heavy and sour(high-sulfur), making it more expensive to extract and refine than the light, sweet benchmarks that command premium prices.

Below is a chart showing Oil Benchmarks Around the World. It maps major oil benchmarks by API gravity and sulfur content, highlighting how far Venezuela and Canada sit from the lighter, sweeter crudes that anchor pricing.

via visualcapitalist

This chart highlights an important reason why the Middle East still has such dominance in the industry. For contrast, Saudi Arabia, with half Venezuela’s reserves, produces 12x more oil daily.

Venezuela’s Production Collapse

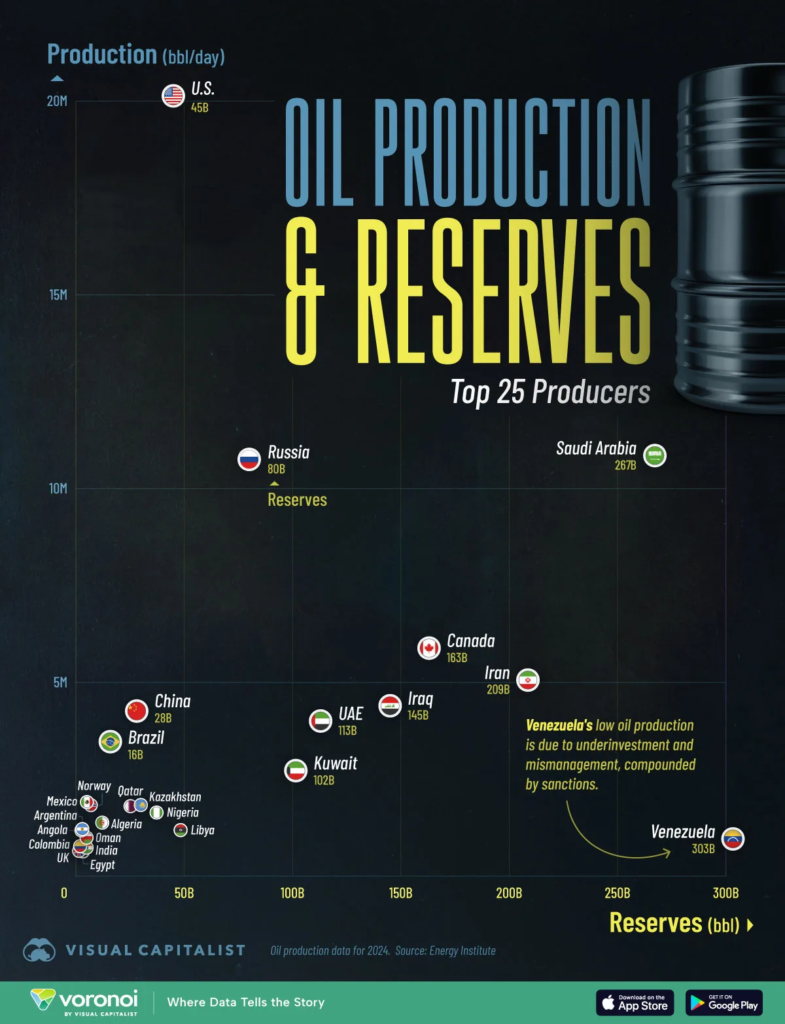

Venezuela is unique among producers, boasting over 300 billion barrels in proven reserves and a reserves-to-production ratio of more than 800 years. It’s the highest in the world by a large margin.

That 800-year figure is a mathematical ratio, not a forecast. It ignores the politics, capital constraints, and shifting demand that will determine whether this oil ever reaches the market.

Put differently, a sky-high reserves‑to‑production number can signal untapped potential or reflect deep structural constraints that paralyze monetization.

In the 1970s, Venezuela’s oil production reached approximately 3.5 million barrels daily, accounting for over 7% of the world’s oil output. Since then, production has fallen drastically due to underinvestment, deteriorating infrastructure, and geopolitical factors such as sanctions. Currently, Venezuela produces approximately 1 million barrels per day, which is roughly 1% of the global supply.

Who Can Actually Produce

Venezuela’s predicament is a lesson in the difference between resource endowment and resource power.

For investors and operators, the real signal isn’t who has the most reserves, but who can turn underground barrels into reliable cash flows at competitive costs.

Here is a chart showing the Oil Production & Reserves of the Top 25 Producers.

via visualcapitalist

The United States leads the list of global oil producers, pumping more than 20 million barrels per day. It also has machinery focused on heavier crude.

With its heavy-crude infrastructure and capital depth, the U.S. may play an outsized role in shaping how Venezuelan reserves are monetized in the years ahead.

The Bigger Picture

All of this is happening against the backdrop of an uneven energy transition: EV adoption, non-OPEC supply growth, and shifting alliances are redefining which barrels matter.

Venezuela’s position serves as a reminder that, in a world gradually decarbonizing, we still remain heavily reliant on oil. As a result, not all crude – or all producers – will be valued equally.

In an era of shifting energy demand, these contrasts underscore how resource endowment and production capacity can tell very different stories, and why future energy security and market dynamics will depend not just on what lies beneath the ground, but on who has the ability (and political will) to bring it to market.

Leave a Reply