This began as a light post, inspired after hearing someone say, “I have an interesting factoid to share …”

I knew they meant a little fun fact. However, the word “factoid” originally meant a plausible-but-false statement repeated so often that it became accepted as fact.

In one of life’s great ironies, it has been misused so frequently that Google now reports both definitions.

In an age where knowledge is instantly accessible, misinformation spreads just as easily — creating a paradox where more data often yields less certainty.

Another amusing example is the word “nimrod,” popularized by the Looney Tunes. Nimrod originally referred to a biblical figure known as a mighty hunter and king. Daffy Duck sarcastically called Elmer Fudd “Nimrod.” Many people didn’t understand the reference, and now a nimrod most commonly refers to someone foolish or unintelligent.

Growing up in the ’60s and ’70s, word of mouth was its own kind of authority. You didn’t have Google, fact-checking sites, or a phone that could settle an argument in seconds; you had whoever seemed the most confident at the lunch table or on the playground. That confidence was contagious. If an older kid swore that swallowed gum stayed in your stomach for seven years, that was it — case closed. The story spread from one backyard to another like gospel, usually picking up new dramatic details along the way. By the time it reached you, it sounded less like a rumor and more like a natural law of the universe.

Myth: A Story As Old as Time

Going back to biblical times, both Jewish and Muslim dietary laws prohibit eating pork. Today, it’s easy to understand why eating pork in the desert was dangerous. Before refrigeration, trichinosis often killed people. So, it’s easy to imagine how people could interpret that as proving God does not want you to eat pork.

What’s funny in hindsight is how these little myths felt like survival guides. Someone would say, “Don’t go swimming for an hour after eating or you’ll cramp and drown,” and suddenly every kid on the block sat on the edge of the pool staring at the clock like they were waiting out a quarantine. No one questioned it because no one could question it.

Myths often persist because they’re simple and socially accepted, while the truth is often messy or inconvenient.

On some level, myths are viruses of the mind, mutating as they pass from host to host. And once a myth becomes entrenched, it becomes part of cultural shorthand, making it surprisingly resilient to actual evidence.

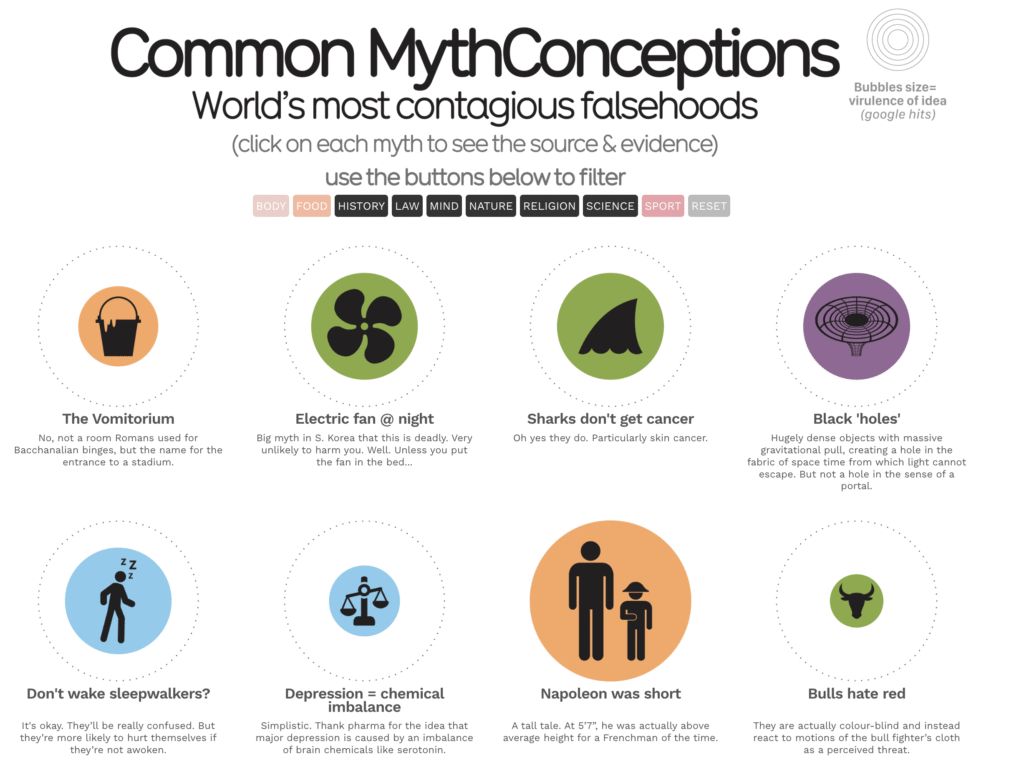

InformationIsBeautiful put together an infographic highlighting some of the most popular misconceptions.

Click the image to go to the full interactive infographic via informationisbeautiful

These misconceptions are so widespread that many people don’t realize they’re mistaken.

For example, humans don’t actually use only 10% of their brains … neuroscience shows we use virtually every region, just not all at once.

Goldfish don’t have three-second memories; in fact, they can remember patterns, signals, and routines for months.

And despite countless school diagrams, Vikings didn’t wear horned helmets … a misconception fermented by 19th-century opera costumes.

These factoids aren’t just fun facts; they illustrate how quickly (mis)information can calcify into belief systems.

For more on this, check out Carl Sagan’s Baloney Detection Kit, which discusses the tools needed for productive skeptical thinking.

Why Myths Endure in the Digital Age

You’d think the digital age would have fixed all this—the moment we gained instant access to unlimited information, it seemed logical that misinformation and mythconceptions would fade away. But in practice, the opposite happened.

Instead of a single neighborhood rumor mill, we now have millions of them, each amplified by algorithms that reward speed, emotion, and repetition over accuracy. Even scarier, some people and entities use technology to boost the spread of disinformation for their own purposes. The same dynamic that allowed a playground myth to spread in the ’70s now operates on a global scale. The internet has given everyone a megaphone, but not everyone a filter, and the sheer volume of voices can make it even harder to tell what’s true. In an almost sadistic twist, the abundance of information made us more susceptible to the myths that feel good, sound right, or simply reach us first.

In a world where information spreads faster than ever, slowing down to check the facts can be one of the most powerful habits we build.

Leave a Reply